There is a sense of elation in the country as India has exported a record 2.12 billion USD (United States Dollar) worth of wheat in 2021-22, which is at least four times more than what was exported in 2020-21. The wheat exports, according to the Union Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Piyush Goyal, are set to cross 10 million tonnes as harvesting picks pace across various states.

In sharp contrast, sarkari mandis where the government directly procures wheat from the farmers at minimum support price (MSP) wear a deserted look. Despite peak season, there are no long queues at the mandis, not even a bunch of farmers, to sell their wheat crop.

The government procurement centre in Uttar Pradesh’s Raniganj village in Unnao has been lying vacant, without a soul in sight. A board for wheat procurement has been put up next to a weighing machine, a destoner machine, which is used to clean the wheat, while empty sacks lie next to it.

“We still haven’t begun the process of wheat procurement at this centre. Five farmers came and got their names noted down, however not even a single farmer has contacted us till now to sell his wheat crop,” Narendra Kumar at the Raniganj procurement centre told Gaon Connection on April 18. “Last year, we had procured close to 6,000 quintals of wheat within the first fifteen days of the procurement cycle,” he added.

Despite the pandemic challenges, Indian wheat exports surged four-fold recording an increase of 273%! #AatmaNirbharKrishi pic.twitter.com/W6dJ5s3e7V

— MyGovIndia (@mygovindia) April 21, 2022

While the officials at the sarkari mandi in Unnao are worried about low procurement, over 900 kilometres away in Punjab, one of the key wheat producing states in the country, farmers are worried about the low crop yield this year.

“Last year I harvested 25 to 30 quintals of wheat on my one acre of land. But this year, the produce is slightly lower than 20 quintals,” Gurbhej Rohiwala, a wheat farmer from Punjab’s Fazilka district told Gaon Connection. “This is due to the severe heatwave last month in March when the temperature suddenly rose within a span of a few days,” he added.

Similar complaints of low wheat yield are pouring in from other states of the country. “I have 15 acres of land. This year, the wheat yield is 17 to 18 quintals per acre, which is a drop of at least three to four quintals per acre as compared to last year,” Harvinder Singh Brar of Rajasthan’s Delwan village in Bikaner district said. “The yield has been affected due to unseasonal rainfall during the sowing season last October, followed by the intense heat in March this year,” the worried farmer added.

Meanwhile, the Indian government is making announcements of increased wheat exports. A week back, on April 15, consumers affairs minister Goyal said that India is targeting to export three million tonne wheat to Egypt in 2022-23 and ten million tonne wheat is to be exported globally for 2022-23.

The increased exports is expected to fill the gap created due to the ongoing war between Ukraine and Russia, the largest wheat exporters of the world, as per the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

A drop in wheat yield in the country this year and the increased exports have worried a section of agricultural experts who are speculating a wheat crisis in the country in the coming months. But there are others who claim India has enough wheat stocks to feed its population and also meet the increased export demand.

Shortage in wheat procurement in India

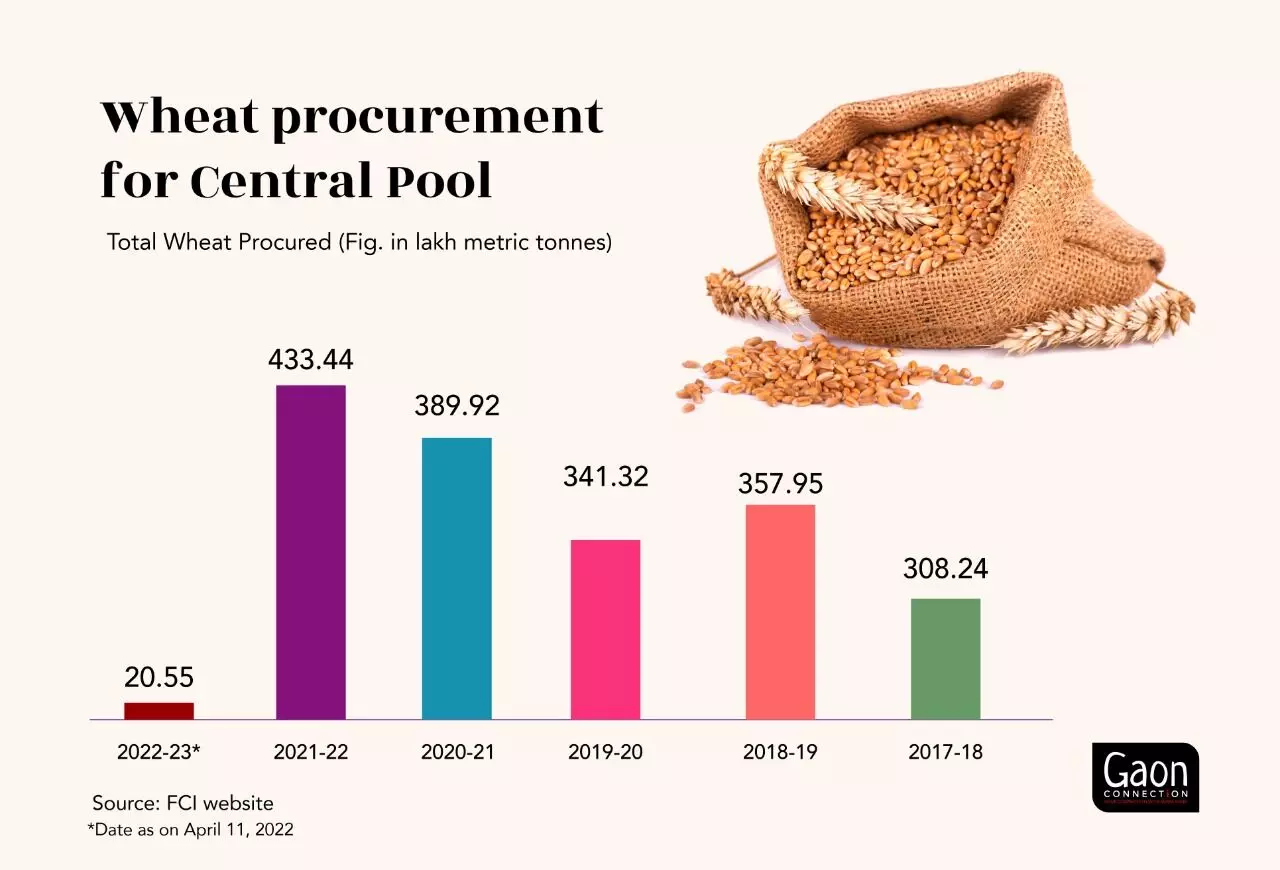

As per the Food Corporation of India’s data, close to 2.055 million metric tonne (MMT) of wheat has been procured from the major wheat producing states in the current rabi marketing season till April 11, 2022.

Exactly a year ago, as per the data released by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution, the wheat procurement figure was 2.924 MMT on April 12, 2021. Thus, a shortfall of 0.869 MMT of wheat procurement this year (see graph: Wheat procurement in India).

“The procurement of wheat by FCI may be lower than usual because the wholesale prices have remained above the MSP in many mandis in contrast to previous year when the wholesale prices were slightly lower than the MSP at this time,” Deepak Johnson, an associate fellow at Foundation for Agrarian Studies, a Bengaluru based non-profit, told Gaon Connection.

The higher prices may continue this year if the exports pick up over time, he said. “There is a general inflationary pressure in the domestic market. Rising fuel prices have been attributed to the increases in wholesale and consumer price indices. Food prices have also increased in the past months, something that may continue in future,” Johnson explained.

However, he went on to add that “the current situation doesn’t appear to be alarming, but reduction in quantity of wheat produced, increase in domestic market prices, and insufficient procurement by the state in the current year may lead to a situation where costs to the poor increase for a period before the next harvest”.

But why are the state agencies unable to procure sufficient wheat in the peak procurement season?

Ankur Trivedi, a wheat farmer from Maholi taluka in Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh, told Gaon Connection, “The MSP for wheat was fixed at Rs 2,015 per quintal by the government. The farmers have been getting a better price for their produce in the open market where at present it is being sold for up for Rs 2,100 a quintal. Hence, all the farmers are queuing up there instead of the government procuring centres.”

In an earlier report, Gaon Connection pointed out how this year farmers have got up to Rs 3,000 per quintal for their wheat crop in the open market. This, experts inform, is due to an increased global demand for wheat due to the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war and disruption of the supply chains.

But, Amit Kumar Dikshit, official at the procurement centre at Sitapur’s Pachasi village, said there was no cause for concern. “The number of farmers who are selling their produce is increasing marginally but since it’s wheat harvesting season, not many have turned up yet,” he said.

Early signs of a wheat crisis?

The data on wheat procurement doesn’t paint a positive picture, Siraj Hussain, a visiting fellow at New Delhi-based Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, and Shweta Saini, an independent researcher, recently wrote in an article.

“As of 18 April 2022, UP procured only about 30,000 tonnes of wheat against 3 lakh tonnes last year. In Madhya Pradesh, too, the procurement is only about half of last year’s. The centrality of Punjab and Haryana in providing food security to India may therefore be proven yet again,” they wrote on April 20.

But, Avinash Kishore, an associate research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, research-based policy solutions think tank, rejected any possibility of a wheat crisis in the country.

“All inputs have become expensive including fertiliser and fuel which means the cost of irrigation where diesel pumps are used, cost of combined harvesting, all of that would have gone up including the cost of bringing grains to the market, hence the market price has also increased otherwise how will the farmers survive,” Kishore asked.

The public-policy expert added that the increase in exports is a big increase compared to the previous exports. However, “it needs to be looked at in tandem with the total buffer stock that the Indian government maintains which makes it rather small in comparison,” he said.

“At best we will be able to export 10 million tonnes this year, so our buffer stock is quite comfortable,” Kishore assured Gaon Connection. “The present situation needs to be looked at from a positive angle as it will help to get rid of the buffer stocks, increase the exports and also help farmers to get a better price,” he added.

On being questioned about the possibility of a shortage of foodgrains for the country’s public distribution system (PDS), Kishore said: “It would be a challenge if we are in a situation where we don’t have enough buffer stock through the PDS system, but we aren’t in that situation. There will be less procurement, this has happened in the past too and in 2006 when there was a similar crisis, the government even had to import because there wasn’t enough stock but I don’t foresee any such situation in 2022-23 or even in the future year.”

“More stock of wheat needed”

India has the world’s largest public distribution system for foodgrains. It has also enacted the National Food Security Act, 2013, which ensures subsidised food grain distribution to 75 per cent of rural and 50 per cent of the urban population. Meanwhile, the Indian government has also launched the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY).

This yojana was launched in March 2020 in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic as massive public distribution of food grains for the poor and is aimed at providing five kilogram (kg) of free wheat or rice per person per month, along with one kg free whole chana per family per month. The scheme has been extended from time to time and is valid till September this year.

“For normal NFSA distribution we will have sufficient stocks but if PMKGAY is further extended beyond September then we may need further stock of wheat,” a senior government official told Gaon Connection on condition of anonymity. “But we expect between 250-300 LMT (25-30 MMT) public procurement this year also,” he assured.

As per the FCI, the current stock of wheat in the central pool for April 2022 is 18.99 MMT which exceeds the buffer norms of 7.46 MMT.

“[Through exports] We may be earning in terms of foreign exchange and that may be good. As far as our PDS requirement is concerned, it’s 245 LMT (24.5 MMT) per annum and we have around 189 LMT (18.9 MMT). We expect procurement around 300 LMT (30 MMT) and even if it comes down to 250 LMT (25 MMT), it would be sufficient to meet our requirements,” the official said.

Worried wheat farmers as crop yield declines

Whereas agricultural experts and the Indian government do not see the present situation to be a cause for concern, wheat farmers are a worried lot as this year their crop yield is low. This is being attributed mainly to the sudden heat wave last month. Many farmers across Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, whom Gaon Connection spoke with, complained of the low production this year as compared to the previous year which they attributed to the heatwaves.

According to news report, wheat yield in Punjab has dipped by more than five quintals per hectare, from 48.68 quintals per hectare last year to 43 quintals this year, because of the intense heat wave in the month of March. The maximum drop were reported in Bathinda and Mansa districts where three farmers died by suicide in the past two days allegedly due to the low crop yield.

As per the 2015 report Climate change and food security: risks and responses by FAO, climate change has already negatively affected wheat and maize yields at a global level.

With inputs from Sumit Yadav (Unnao), Ramji Mishra (Sitapur) and Virendra Singh (Barabanki) in Uttar Pradesh.