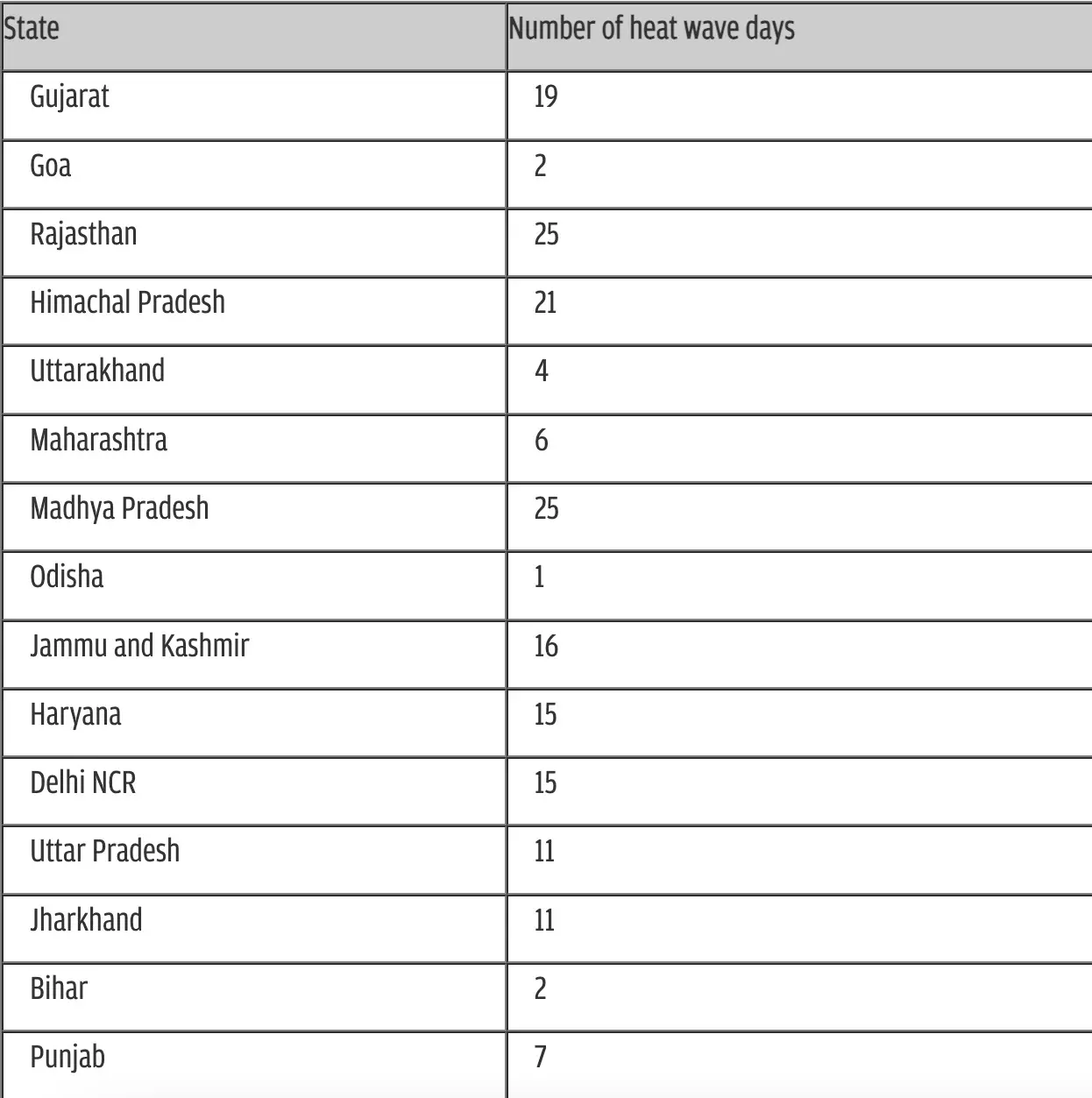

The states of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh have suffered the most due to a series of heatwaves in the country this summer. As of April 24, the early heatwaves of 2022 began on March 11 and have impacted 15 Indian states and Union territories.

Of these, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh have witnessed 25 heatwave and severe heatwave days so far. This is followed by the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh, which has recorded 21 heatwave and severe heat wave days since March 11 this year.

These are some of the key findings of the India Meteorological Department (IMD) data analysed and recently released by New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). The analysis has been published in CSE’s fortnightly magazine, Down To Earth.

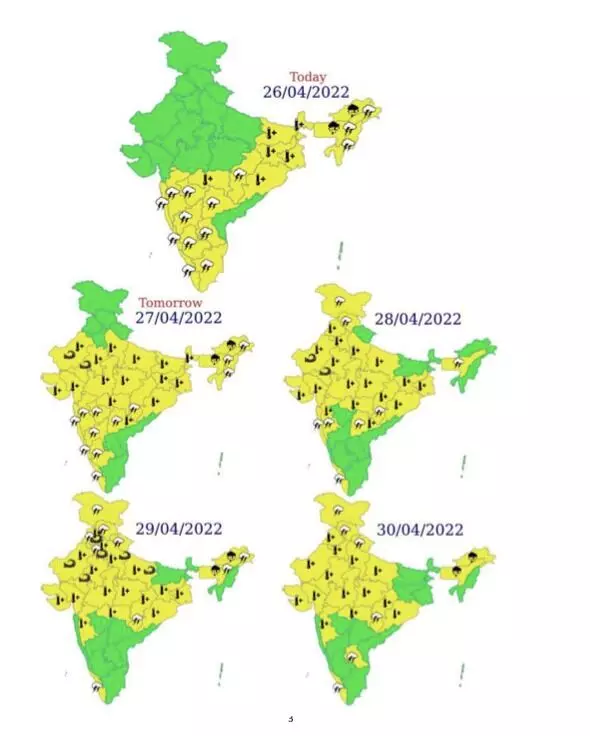

Meanwhile, the IMD has issued a heatwave alert today, April 26, warning of “Heat wave conditions over east India during next 4-5 days, likely to commence over central, northwest & west India from 27th April, 2022.”

Photo by: IMD

Why the heatwave?

“Anti-cyclones over western parts of Rajasthan in March and the absence of rain-bearing Western Disturbances had triggered the early and extreme heat waves. Anticyclones cause hot and dry weather by sinking winds around high pressure systems in the atmosphere,” D Sivananda Pai of the Kottayam-based Institute for Climate Change Studies was quoted by CSE.

According to the Met department, a heat wave happens when the temperature of a place crosses 40 degree Celsius (C) in the plains, 37 degree C in coastal areas, and 30 degree C in the hills. If a place registers a temperature that is 4.5 – 6.4 degree C more than the normal temperature for the region on that day, then it’s declared a heatwave whereas if the temperature is over 6.4 degree C more than the normal, the IMD declares a ‘severe’ heat wave.

Photo by: CSE

Another criteria, observed by CSE, for declaring a heatwave is based on absolute recorded temperatures. If the temperature crosses the 45 degree C mark, the IMD declares a heat wave; when it crosses 47 degree C, a ‘severe’ heat wave is declared.

Impact of heatwaves

The CSE analysis pointed out that heat waves exert enormous impacts on health, agriculture and availability of water – all often related to each other in complex ways.

“Even though the number of deaths due to heatwaves in India has decreased over the years, research shows that the general physical and mental wellbeing of people does get affected by extreme temperatures. On the other hand, agricultural yields get impacted as well,” it noted.

Citing the example of how wheat crop in the current rabi season in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh has been impacted by heat waves, CSE observed: “Many farmers have reported losses between 20 and 60 per cent in these states. This happened because the heat waves were early this year and the temperatures affected the wheat plants during their growth stage, leading to shrivelled grains which fetch lower prices in the market, resulting in losses.”

The research group has suggested that in order to reduce agricultural losses due to heatwaves, heat-tolerant varieties of wheat need to be developed. Similarly, it also suggested that heat-resistant varieties of other rabi crops need to be developed.

“Apart from direct heat, agricultural yields may also get impacted by droughts or drought-like conditions that are often associated with heat waves. This mainly occurs because of non-availability of water for irrigation during drought conditions,” the CSE analysis revealed.

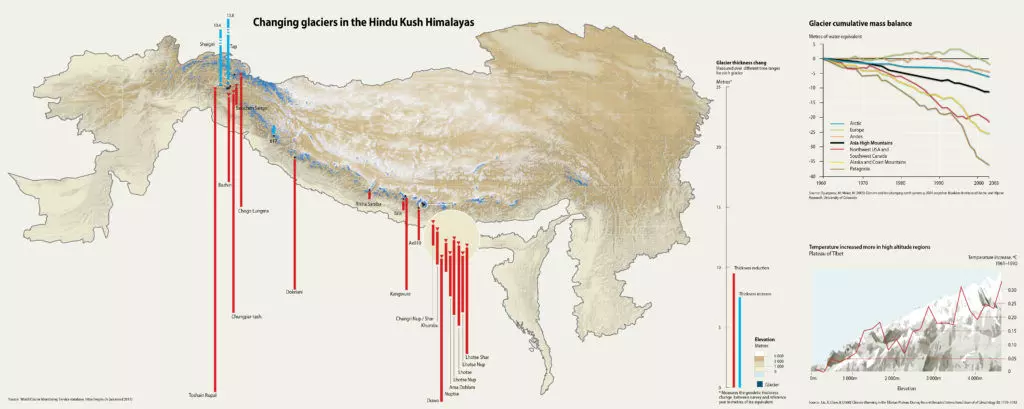

The detailed analysis also pointed out that the unlikely impact of the current heat waves would occur in the Himalayan regions of Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Uttarakhand that are not used to heatwaves and not well adapted to the extreme temperatures.

“One major impact in these regions would be on the accelerated melting of glaciers due to extreme temperatures which are the main source of water for the people living there,” it added.

What does the recent IPCC report say about the heatwaves?

The recently released sixth assessment report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) revealed that there is increasing evidence of climate action but without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, limiting global warming to 1.5°C is beyond reach.

The report’s assessment highlighted that limiting warming to around 1.5°C (2.7°F) required global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43 per cent by 2030.

It also observed that the global temperature will stabilise when carbon dioxide emissions reach net zero.

“For 1.5°C (2.7°F), this means achieving net zero carbon dioxide emissions globally in the early 2050s; for 2°C (3.6°F), it is in the early 2070s,” the report stated.

It also outlined that as per this assessment, limiting warming to around 2°C (3.6°F) still requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by a quarter by 2030.