Last year, Mohammad Ufran sold four

handlooms, a warping machine and a binder that he had bought with hard-earned

money as scrap and opened up a kirana store in his village. In order to

supplement his income, he has even placed a sewing machine in the shop.

Ufran, 55, is a resident of Bijnor’s

Serahvillage, which is about 175 km from Delhi. Previously known as the

handloom hub, Bijnor now witnesses several handloom units closing down. People are

wrapping up their ancestral trade are resorting to other means of livelihood.

Gaon Connection reached Serah to find

Ufran sitting at his Kirana shop. Upon being asked the reason for wrapping up

of his earlier work, he said: “In 2013, when I began working, my work thrived,

but then losses followed the note-ban and the subsequent Goods and Services Tax

(GST) made the goods expensive. The labour moved elsewhere. Forcibly I had to

sell my machines in scrap last year where the machines costing Rs 2.5 lakh,

fetched me Rs 25-30,000.”

Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district is

well known for its handloom craftsmanship. About 35 kms far from the district headquarters,

Nathaur had, till some time ago, every house engaged in handloom craft. But now

this trade survives even less than 50%. As per the traders, while the village

had 2.5 lakh machines installed once, their number has now dwindled to barely a

45,000.

Mohammad Ufran

Mohammad Ufran

Besides Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh’s

Azamgarh, Varanasi, Bhadohi, Mirzapur, Ghazipur and many more districts engage

in handloom craft. As per the 2009-10 Handloom Census, 43 lakh people in the

country are associated with this trade. But since the last decade, the handloom

work has witnessed a sharp decline.

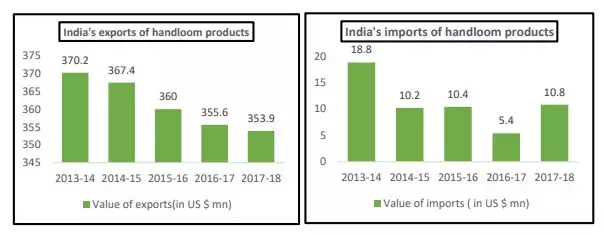

As per a report of Export-Import Bank

(EXIM), the total Indian handloom products export for the year 2013-14 was

worth Rs 2,474 crore. It came down to Rs 2,444 crore in 2014-15.

The decline continued in 2015-16 to Rs

2,394 crore, Rs 2,365 crore in 2016-17 and in 2017-18 the total export had

registered Rs 2,354 crore. Once India leads the handloom product export in the

world with a 95% share in the international markets.

The state of imports clarifies the

total scenario. In the year 2013-14, the country’s import of handloom product

was worth Rs 125 crore with a minor dip in 2014-15 to Rs 67 crore it improved in

2015-16 to Rs 69 crore.

But the very next year, the imports

dropped to Rs 35 crore whereas in 2017-18 it showed a remarkable rise to Rs 71

crore telling of the present state of the Indian handloom industry.

As per the records of Ministry of

Textiles, Government of India, employment, along with the production, has gone

down substantially in the handloom industry. Annual production of handloom

textiles have fallen from 64,333 million sq meters in 2014-15, to 63,480

million sq meters in 2016-17.

The turbulent times faced by this

multi-million-dollar industry, depicted in the formidable statistics of these

records have begun showing the impact on normal life as is witnessed in places

like Bijnor. Bijnor’s Nathaur, Phoolsanda, Sedhi, Sedha, Milak, Karaunda,

Rawana Shikarpur, Basta, Pipali, Syohara, Tajpur, Nurpur, Chandpur, and

Naginaetc, were known for weaving.

This district of Uttar Pradesh used to

attract weavers from across the country. The scarves, stoles, turban cloth,

bedsheets and mufflers woven here were sold widely India and internationally.

Nathaur region’s 100 villages used to work with the handloom-power loom, including

Sedha which is now devoid of the activity.

When we approached the seniormost

trader of Sedhavillage, Zulfekar Ali, 53, we found him fanning himself with a

hand-held fan, surrounded by people who had gathered in his house to celebrate

the wedding in the neighbouring house.

Being inquired about the state of

handloom, he said: “You can see for yourself what the situation is. It is 2 PM

and there isn’t any electrical supply since 10 PM last night. In such heat we

cannot function without electricity. There isn’t any more work. Whatever little

work of the local market we get, the craftsmen begin working upon as soon as

the power resumes. I had 10 power loom machines out of which I’ve sold eight. The

remaining two perform whatever work comes our way.”

In the textile industry, hand operated

machines are called handlooms and electricity run machines are called power looms.

How did the industry get hit? Zulfekarsaid:

“It’s not that our work stopped suddenly. Note ban had resulted in cash-flow

problems for us. Labourers abandoned their work and left due to which the

existing orders could not be executed. Due to this, we were unable to secure

fresh orders so power loom or handloom—everything came to a stop. Powerloom also

require human effort to operate it.”

Talking about the implications of the

GST, he said: “We pay 12% tax on raw material while the same material when

processed attracts only 5% tax, this means we suffer a loss of 7%. The government

says that cloth made from the raw material is sold at an escalated price and so

doesn’t return us our money.”

Zulfekar’s two sons who used to assist

him have left to work in cities. Zulfekar resigns saying, “Employing 10-12

regular workers earlier, it so came to pass that today my own sons have to work

for someone else.”

Just like Bhadohi’s carpets, the

craftsmanship of this place was much appreciated in the US and European

markets. Introduction to power loom didn’t bring any significant change.

“The district’s annual handloom

turnover used to exceed Rs 250 crore, but now it has shrunk to Rs 50 crore,” Jalauddin,

51. He had been one of the districts’s top exporters with his own eight machines. He

said: “The local handloom industry was employing over 15,000 individuals

directly and over 80,000 indirectly. The whole network has evaporated into thin

air.”

Jalaluddin is one of those people

doing handloom work across generations, but the present state of the industry

disappoints him. His tone betrayed helplessness when he said: “Previously our

workmanship used to be appreciated widely, but with China’s foray in the market

our business suffered. The situation took a worse turn from 2016—first note-ban

and then GST. We could not recover fully from these two setbacks. The state

government’s apathy on the matter is not helping the situation either.”

Bijnor’s entrepreneurs suffer a major

setback of erratic power supply with prolonged power cuts. Jalauddin tells,

“The government claims that it is supplying 17-18 hour’s electricity whereas

the reality is in front of you. Rate of payment has also been increased. With

the increase in cost, we are left with no alternative but to close our

operation. Previously we used to work full days amid the constant din of handloom

machines, but now we are left lamenting over our inability to keep alive our

ancestral trade.”

The country’s textile industry

currently suffers from a slump. The Northen India Textile Mills Association’s

report shows that the country’s textile business is in the worst phase of the

past 10 years. Last time the industry faced such slump only in 2010-11.

In the trimester April-June2019, the

export of cotton-based products has fallen by over 34%. Last year, about the

same time, this trade recorded a turnover of $1,063 million which has plummeted

this year to $696 million.

The Nation’s 10 crore people are

employed in the textile sector which contributes 2% of the national GDP. With

the fall in the trade, lakhs of people have lost employment.

Nathaur’s Afsar Ahmed, 41, weaves

himself and offers employment to others. Explained the jump in input costs, he

said: “A 2 meter long and 28inch wides stole takes 2-3 hours to be woven. Just

weaving costs Rs 80 whereas we get Rs 78-80 in the market as its price. If we

get Rs80, we breakeven, anything less we incur a loss. We used to earn Rs15-18

per piece when the input cost was low.”

As per Afsar, he doesn’t do any work

following the GST and he is also not aware of it, but he knows for sure that

electricity bills have gone up, the price for cotton yarn has gone up, but his

profit hasn’t.

West Bengal leads the country in the handloom industry followed by Andhra Pradesh. Mohan Rao, head of Andhra

Pradesh’s nationwide NGO Rashtra Chetna Jan Samakhya, told Gaon Connectionoverover

the phone: “It’s a fact that the government is itself responsible for the

current situation. A look at the budget can clarify government’s intent which

had sanctioned Rs 621.51 crore for the textile sector in 2014-15 and thereafter

reducing to Rs 486.60 crore in the year 2015-16. However, the said amount was

increased substantially in 2016-17 to Rs 710 crore.”

He added: “The budgetary cuts began

thereafter—for 2017-18 the amount was reduced to Rs 604 crore and further

reduced in 2018-19 to Rs 386 crore. For 2019-20, the amount was improved

marginally to Rs 456.80 crore. But still, the budgeted amount remains less than

the one sanctioned in 2014-15.”

Last decade has seen a decline in the

sector with hardly any development of new employment opportunities. As per the

third Handloom Census 2009-10, the country had 43 lakh weavers whereas the

second Census showed 65.5 lakh weavers employed in the sector. Fourth Handloom

Census was to be declared in 2017 but has not been so far.

Mohan Rao said: “The government had

promoted automation at the cost of handiwork. Our workmanship was our hallmark

which helped popularize our products internationally. Everyone has machines.”

The truth of Mohan Rao’s allegations

resonates about 2000kms far from Andhra Pradesh in exporter Mohd Shahid’s

godown at Bijnor’s Mohalla Nohada in Nathaur. The godown maintains a stock

worth about Rs 25 lakh but has no buyer. Shahid’s scarves were well sought

after in the European markets, but today his production has almost closed down.

Shahid said: “This stock is lying for

the past-one-and-a-half year for want of a buyer. I too have started crockery

business. Previously I employed 50-60 people. Many village women used to come

here to earn for their families, in order to marry off their daughters, but now

we being ourselves out of work can hope little to help others.”

Removing dust off the bundles of

clothes shahid added: “After closing our export unit, we attempted the local

market, but the prices were quite low. I now have barely 10% of the work

remaining. Not only my work but also that of yarn dyers, knitters and binders

has come to a stop.”

KP Verma, deputy commissioner of Uttar Pradesh’s

Handloom and Textiles Industry has a different take on the entire issue. He

informed Gaon Connection over the phone: “Although it is a fact that the

handloom trade is on a decline, the government is not responsible for it.

The younger generation doesn’t believe in exhorting itself which resulted in

the increased use of power looms. As for the government, it is running several

schemes to benefit the handloom industry.” He added that the field has shown

tremendous competition with immense choices for the consumer. This also

contributes to the slowdown in the handloom industry.

But in Bijnor presently even power looms have fallen silent. As per the records of Indian Ministry of

Textiles, out of total textile production in the country, handloom occupies 20%,

weaving comprises 15% and power loom comprises 60% besides 5% contributed by

other organized sectors.

The country currently has 19.42 lakh power looms in operation providing employment to about 70 lakh people.

Also Read: “It’s been months since I paid my kids’ school fees”: Kashmiri carpet weaver