1,300 metres above mean sea level. Kullu, Himachal Pradesh.

Padam Dev, a pomegranate farmer in Mamjiya village of Kullu district in Himachal Pradesh, has grown up hearing stories of his father and grandfather’s apple orchards. He hasn’t been able to grow even a single apple fruit in his orchard in Banjar block, about 170 kilometres (km) from the state capital Shimla. “Now there isn’t enough winter chill and cold months to grow apple in my village,” he told Gaon Connection.

Over 2,000 km away, at an elevation of 2,500 metres above mean sea level, 92-year-old Til Bahadur Chhetri of Hee Patal village in West Sikkim is worried about the declining yield of his black cardamom (Amomum subulatum) crop. “The rains have become erratic and temperatures are rising bringing in new pests,” lamented Chhetri.

Another 600-km away, 54 per cent surveyed springs in Meghalaya have reported reduced water discharge of up to 50 per cent, threatening the water security of the north-eastern state. Both villagers and water sector experts blame it on the changing rainfall pattern (coupled with some other factors).

92-year-old Til Bahadur Chhetri in West Sikkim is worried about the declining yield of black cardamom. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

92-year-old Til Bahadur Chhetri in West Sikkim is worried about the declining yield of black cardamom. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

The Indian Himalayan Region, covering over 16 per cent of the India’s geographical area and home to over 50 million people, is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts.

To understand the extent of vulnerability, for the first time a scientific assessment of climate vulnerability of states in this region has been carried out using a common framework of indicators.

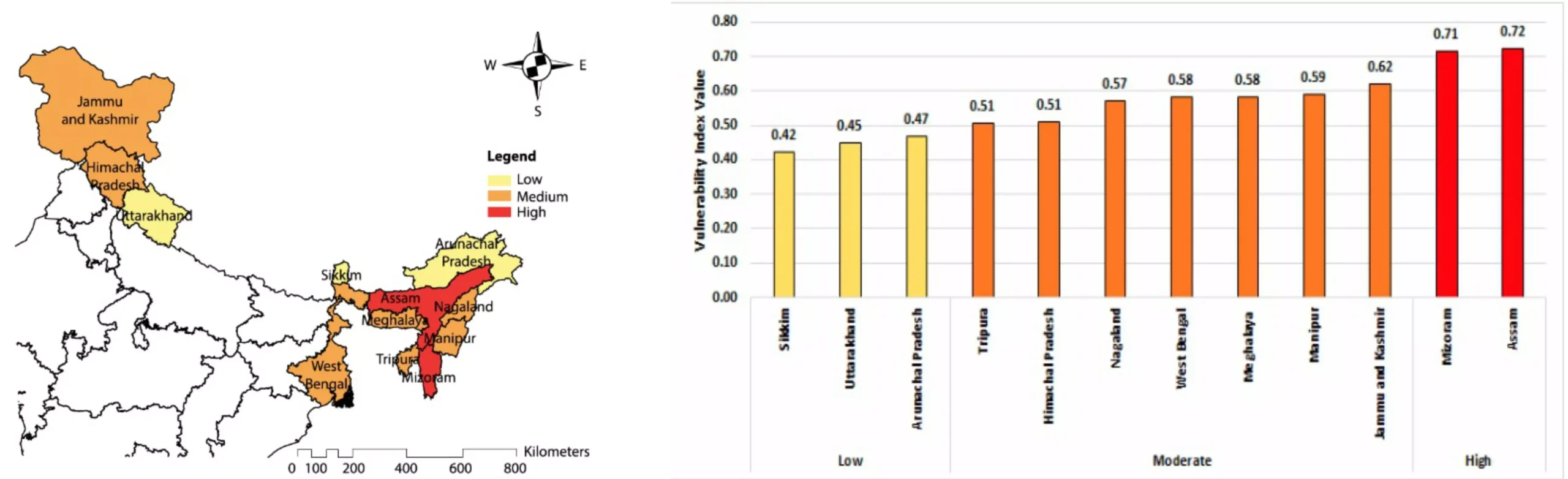

Titled ‘Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework‘, the assessment report maps and ranks all the 12 states in the region (only the hill districts of Assam and West Bengal) based on how vulnerable they are to climate change (see map: Vulnerability index and ranking of states in the Indian Himalayan Region).

Map: Vulnerability index and ranking of states in the Indian Himalayan Region

Source: Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework 2018-19.

Source: Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework 2018-19.

Assam is ranked number one on the climate vulnerability index followed by Mizoram and Jammu & Kashmir. Sikkim, as per the report, is least vulnerable to climate change in the Indian Himalayan Region.

The vulnerability index values for all the 12 states have been arrived at using four broad, common indicators. These include socio-economic, demographic status and health; sensitivity to agricultural production; forest dependent livelihoods; and access to information services and infrastructure. Other sub-indicators include per capita income, percentage area irrigated, area under forests per 1,000 households and percentage area under open forests.

This scientific assessment has been carried out by the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Guwahati and IIT Mandi, in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. It has received support of the Department of Science and Technology and the Swiss Development Corporation, which is implementing the Indian Himalayas Climate Adaptation Program (IHCAP).

“Till now the states carried out their own vulnerability studies using a varied set of indicators, which were not comparable. For the first time, we have used broad but common indicators for mapping and ranking all the states in the Indian Himalayan Region,” said Anamika Barua, associate professor, department of humanities and social science, IIT Guwahati. She is the principal investigator of the assessment report.

“Whereas all the states in the region used the same set of indicators, they were free to give different weightage to the chosen indicators keeping in mind the ground situation in their respective states,” she explained. The states have further prepared their own district level vulnerability profile using common indicators with different weights, she added.

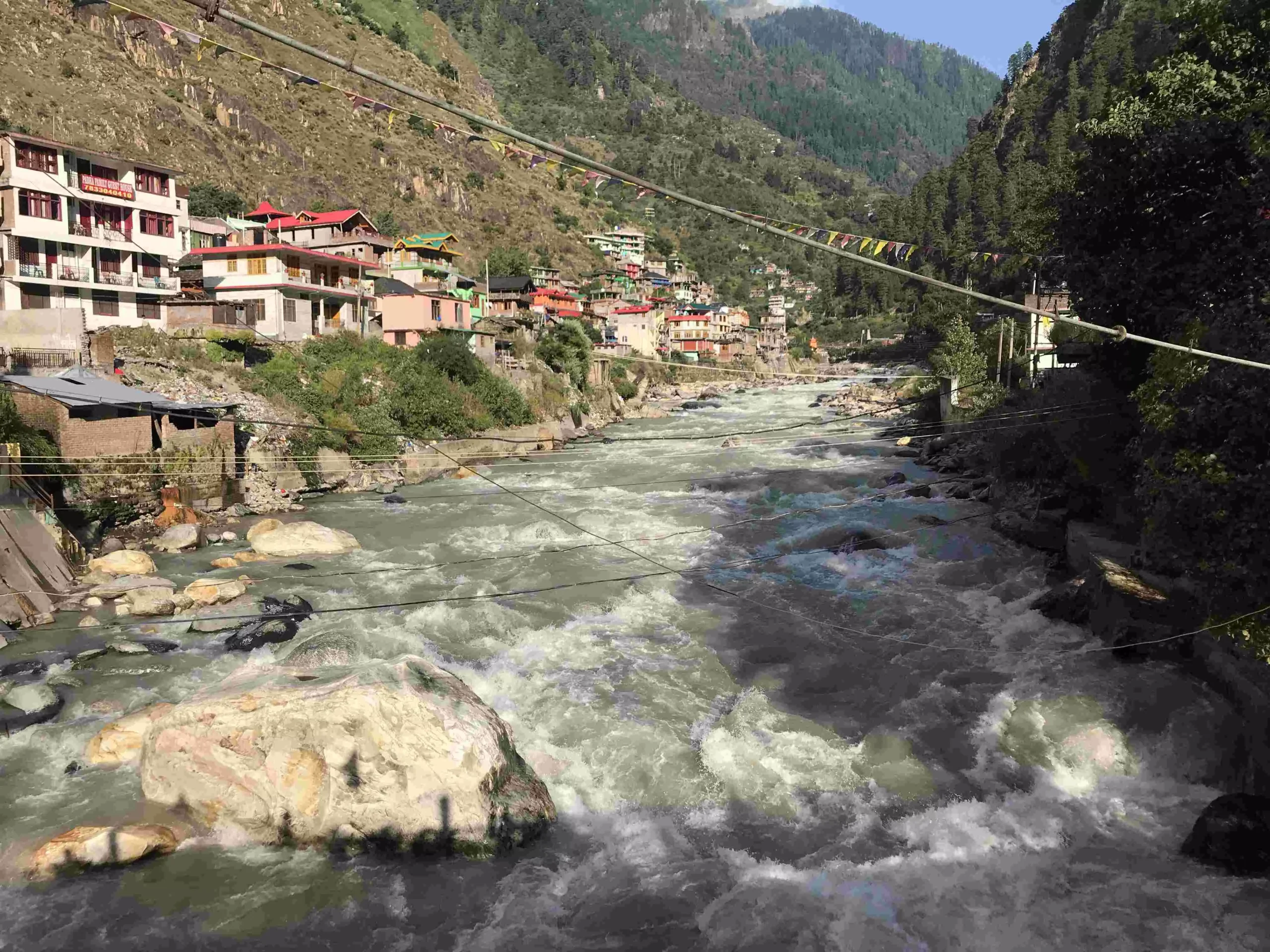

Climate vulnerability assessment of all 12 states in the Indian Himalayan Region has been carried out. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Climate vulnerability assessment of all 12 states in the Indian Himalayan Region has been carried out. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Explaining the rankings, Mustafa Ali Khan, team leader with IHCAP said: “All the states in the Indian Himalayan Region are vulnerable to climate risks. The vulnerability is a relative measure meaning states like Sikkim or Uttarakhand have low vulnerability when compared with Assam or Mizoram.”

Commenting on the assessment report, Akhilesh Gupta, adviser and head of climate change programme, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India said: “The recent report on climate vulnerability assessment is an important scientific document that assesses and maps vulnerability in all the states of the Indian Himalayan Region. We plan to extend this exercise of climate vulnerability assessment across the entire country.”

According to Khan, to understand vulnerability, it is important to understand hazard and exposure. “Hazard includes events such as landslide or drought, etc. Exposure shows the number of people exposed to a particular hazard. Not all people exposed to a hazard are equally vulnerable.”

For instance, in case of a natural disaster, children or young women or poorest of the poor may be more vulnerable. Vulnerability assessment helps build suitable programmes, policies and adaptation measures.

Vulnerability assessment helps build suitable programmes, policies and adaptation measures. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Vulnerability assessment helps build suitable programmes, policies and adaptation measures. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Assam most vulnerable to climate change

According to the climate vulnerability assessment report, there are various reasons (indicators) that make Assam highest vulnerable to climate change in the Indian Himalayan Region. These include least area under irrigation, least forest area available per 1,000 rural households, second lowest per capita income; low percentage area covered under crop insurance and low MGNREGA [Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act] participation.

The report goes on to note that “lack of access to information and infrastructure puts this state into a situation where it would be extremely difficult to cope with any climate extremes”.

In case of Mizoram, which is ranked number two on the climate vulnerability index, the assessment report identifies various drivers of vulnerability -– highest yield variability; no area under crop insurance; largest area under open forests; and largest area under slope >30% as compared to other states.

Mizoram also has the second lowest percentage area under irrigation and the third lowest road density among the 12 states included in the assessment study.

Assam is ranked most vulnerable to climate change whereas Sikkim is least vulnerable. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Assam is ranked most vulnerable to climate change whereas Sikkim is least vulnerable. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Somewhat similar drivers of vulnerability are identified for Jammu & Kashmir — least road density; no area under crop insurance; low area under forests per 1,000 rural households; high percentage of marginal farmers; low percentage area under horticulture crops; low livestock to human ratio; and low percentage of women in the overall workforce.

“Impacts of climate change are already being felt in the state. Both our annual mean maximum and annual mean minimum temperature is on a rise, but precipitation is on a decline,” said Majid Farooq, scientist and state coordinator, state climate change centre, Government of J&K.

This is not all. “The annual stream flows in our three main rivers — Indus, Chenab and Jhelum — is on a decline. The area of Kolhoi glacier, which is a major source of fresh water supply to the Kashmir valley, has reduced from 112.33 square kilometre in 1911 to 94.44 square kilometre in 2014,” he added.

Nagaland, which is ranked seventh in the climate vulnerability index, also has no coverage under crop insurance, low percentage of farmers taking loans and low area under forests per 1,000 rural households. But, the state “has high per capita income, low population density, lowest prevalence of marginal farmers and highest women participation in the labour force that make the state relatively resilient”, notes the assessment report.

Tripura, ranked ninth, has the highest road density, lowest area under slope >30%, highest MGNREGA participation and lowest yield variability when compared to other states in the region.

Similarly, Arunachal Pradesh, ranked tenth, has the least population density and the most densely available healthcare facility among all the 12 states. It also has a relatively low percentage of marginal farmers and high women participation in labour force that reduces the overall vulnerability of the state.

Sikkim, which is considered least vulnerable to climate change in the Indian Himalayan Region, “has the highest per capita income and the lowest area under open forests”.

The assessment report notes that “the drivers of vulnerability of different states in the IHR [Indian Himalayan Region] are diverse in nature. Hence while formulating adaptation measures, there is no one panacea that can be applied to all the states.”

High women participation in labour force reduces the overall vulnerability of the state. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

High women participation in labour force reduces the overall vulnerability of the state. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

District-level vulnerability assessment

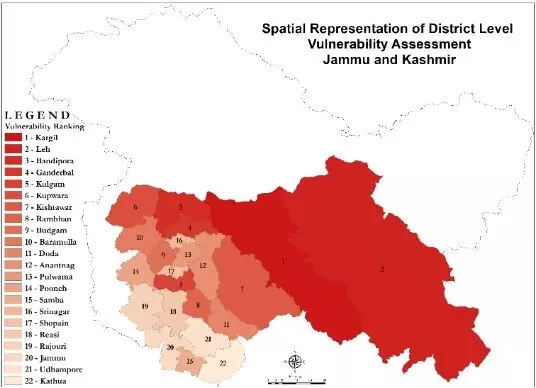

The scientific assessment of climate vulnerability has not remained at the states’ level. All the 12 states in the Indian Himalayan Region have also prepared their own district-level vulnerability maps and ranked various districts on the basis of chosen indicators. These district-level maps are part of the ‘Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework‘ report.

“Vulnerability assessment carried out at block or district level can depict the profile of vulnerability at the state level showing blocks and districts under different vulnerability categories such as low, medium and high vulnerability. Such information helps in the identification of priority blocks/districts for resource allocation, prioritising the allocation of adaptation funds and adaptation interventions,” reads the report.

In case of Assam, which is ranked number one on climate vulnerability index, Dhubri district is most vulnerable to climate change and Sivsagar least.

In case of Mizoram, Siaha district is most vulnerable because it has “third largest steep slope coverage among all districts, is fourth in lack of forest cover and third in lack of person days generated under MGNREGA.”

Similarly, district-level assessment carried out in Jammu & Kashmir found Kargil district to be most vulnerable and Kathua to be least vulnerable to climate change (see map: District level vulnerability assessment in Jammu & Kashmir).

“Kargil has three major drivers of vulnerability —- lowest per capita income, largest area under slope >30% than other districts and high infant mortality rate,” informed Farooq.

“We have also prepared social vulnerability index map and economic vulnerability index map of all the districts in the state,” he added.

Map: District level vulnerability assessment in Jammu & Kashmir

Source: Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework 2018-19.

Source: Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region Using a Common Framework 2018-19.

Now that all the states in the Indian Himalayan Region have prepared their climate vulnerability maps, they need to prepare a good adaptation framework incorporating the findings of vulnerability assessment.

This is crucial because the Himalayan region is at a great risk of climate change. A 2010 study on the Himalayan region, commissioned by the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change, has reported that minimum temperatures in the region are projected to rise by 1 degree C to 4.5 degree C, and the maximum temperatures may rise by 0.5 degree C to 2.5 degree C.

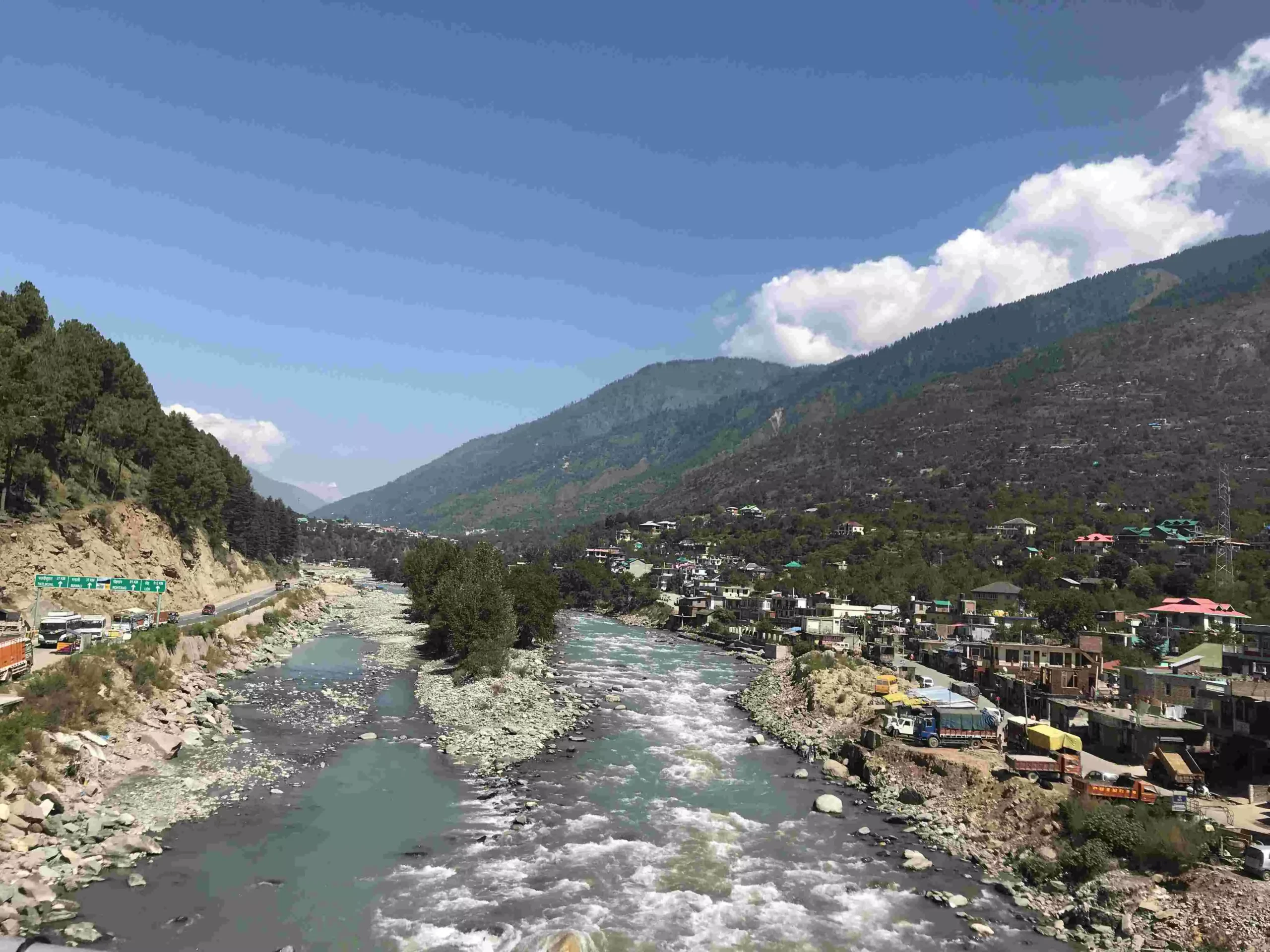

Flash floods due to glacial lake outburst floods may lead to large-scale landslides. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

Flash floods due to glacial lake outburst floods may lead to large-scale landslides. Pic: Nidhi Jamwal

The increase in temperatures may lead to increasing morbidity due to heat stress. Flash floods due to glacial lake outburst floods may lead to large-scale landslides and affect food security.

The same study of the environment ministry supports Padam Dev, a pomegranate farmer in Mamjiya village of Kullu, comment on disappearing apple orchards. It notes that between 1982 and 2005, apple production in the Himachal region has decreased due to an increase in maximum temperature which has lead to a reduction in total chilling hours in the region — a decline of more than 9.1 units per year in the last 23 years.

It is clear that changes in temperature and precipitation will have serious and far-reaching consequences on climate-dependent sectors, such as agriculture, water resources and health in the Indian Himalayan Region.

The science is clear. The vulnerability maps are ready. Will the policy-makers and bureaucrats act now?