Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh

Sunaina is 15-year-old and lives in Bhopal, the capital city of Madhya Pradesh. As a child, she lived in Badivir village next to a jungle in Vidisha district, and roamed around all day, gathering firewood from the forests, hunting birds or picking fruits and berries.

“While we were registered at the village school, we could never study there. We roamed around the jungle the whole day,” Sunaina told Gaon Connection.

But that was over a decade ago. Sunaina now enjoys writing and many of her stories in Hindi have been published by Ektara and Chakmak publishers. The 15-year-old is currently studying at an ITI (Industrial Training Institute) in Bhopal.

Sunaina’s younger sister, 13-year-old Jaya, who also used to roam around the jungle, is now studying in Bhopal and is in the tenth grade. “I love doing theatre and I have performed in many places along with IPTA [Indian People’s Theatre Association], the theatre group,” she told Gaon Connection.

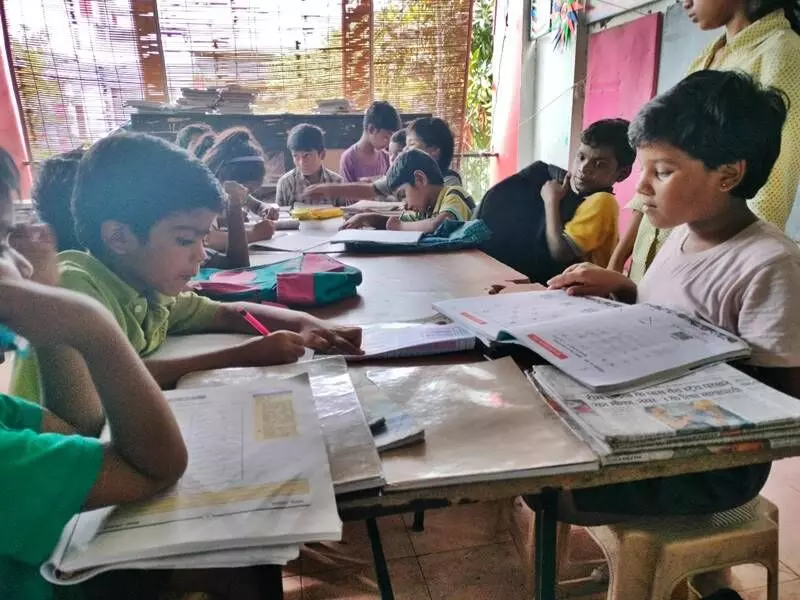

The primary and middle school children who live in the Aranyawas hostel study at the government higher secondary school at Bawadia Kalan in Bhopal.

The story of Sunaina and Jaya is highly inspirational and a matter of great pride because these sisters are the first two Pardhi girls to study up to the high school in Vidisha district of Madhya Pradesh. The Pardhi is a denotified tribe, which is infamous for early girl child marriages (10-12 years).

And had it not been for Aranyawas, a Bhopal-based non-profit, Sunaina and Jaya may well have been married too. But, for the past one decade, the Pardhi sisters have been living at a home-cum-hostel run by Aranyawas, which is especially meant for the Pardhi community children.

“Aranyawas runs a home for Pardhi children between five and 14 years of age, as well as for children who are from non-notified communities, who stay here in Bhopal to get an education,” Archana Sharma, director of Aranyawas, told Gaon Connection. Aranyawas works in the area of biodiversity conservation, and the Pardhi community, being a traditionally nomadic hunting tribe, has excellent knowledge of flora and fauna.

The Pardhi community once lived in forested areas and their sustenance and livelihoods depended on hunting and trading in forest produce. Its community members inhabit parts of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra. Pardhis are more than marginalised (social stigma), are not part of any rehabilitation schemes and lead a life of limbo, said Sharma.

“They lead very precarious lives. And, ever since the Wildlife Protection Act was passed in 1972, they were forced to abandon their traditional occupation and now struggle to survive,” she added.

“We learnt that the children of this tribe are unable to find a place in village schools to get an education. They face discrimination and prejudice from others, as a result of which they have not been able to get an education. We decided to change that,” the director of Aranyawas said.

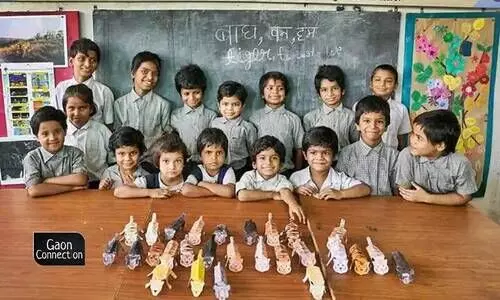

Aranyawas, a home for the Pardhi children

Aranyawas was established about eleven years ago to function as a hostel for the children of the nomadic and denotified tribes. These children stay at Aranyawas for free.

“We started this hostel with just two children, now we have 30 children who come from across Madhya Pradesh,” said Sharma. The parents of these children move from village to village selling bangles, herbs or collecting discarded plastic bags, she said.

At Aranyawas, the effort is to make the children comfortable. “We encourage them to nurture their knowledge and love for Nature to protect biodiversity. We make sure that they stay in touch with their language and cultural identity,” she said.

For 17-year-old Umesh, staying in Aranyawas provided an opportunity to pick up the Gond style of tribal art. “A Gond artist came to our hostel a few years ago and I learnt the techniques from him in the four days he taught us. After this I took part in a six-day Gond painting workshop at the Tribal Museum in Bhopal,” Umesh told Gaon Connection.

For 17-year-old Umesh, staying in Aranyawas provided an opportunity to pick up the Gond style of tribal art.

Umesh now paints on canvas with considerable skill. “My experience of the forests, the creatures who live in it, all that I have seen there, I try to transfer it to the canvas with my brush,” he said. Umesh lost his father to tuberculosis three years ago and his mother goes from village to village selling bangles.

Also Read: Pardhi tribe members still roam the forests of Madhya Pradesh — as nature guides, not hunters

“The children who came to the hostel had initial problems adjusting. We too took a while to understand them. They took time to understand the language as they were only exposed to the Pardi dialect,” Pooja Parmar, warden of Aranyawas hostel, told Gaon Connection.

“These children are not like the others who grow up in one place under the care and protection of their parents. The Pardhi children are free-spirited, are used to moving frequently. Keeping them confined to one place has been the biggest challenge,” Parmar said. But they were bright, alert and quick to pick up their lessons, she added.

These children stay at Aranyawas for free.

The primary and middle school children who live in the Aranyawas hostel study at the government higher secondary school at Bawadia Kalan in Bhopal.

“Our teachers pay special attention to the children of the Pardhi community,” Arvind Srivastav, the teacher-in-charge at the school, told Gaon Connection. “Like any other children there are some who are good at studies and others who excel in sports. They are here to get an education so that they can erase the tag of belonging to a ‘criminal tribe’,” Srivastav added.

Also Read: Gadia Lohars in Datia want stability

Tag of criminal tribe and early marriage

The British had declared the Pardhi community as a ‘criminal tribe’ through the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Post independence, the Indian government denotified the tribe in 1952, but seven decades later, the Pardhi community still remains marginalised and faces social stigma.

“As a consequence of the tag of criminal tribe, Pardhis were looked upon as lowly and dangerous,” said Sharma, the director of Aranyavas. They were denied access to education, employment, and basic infrastructure. They do not even fall under the Schedule Caste, Schedule Tribe or the Other Backward Class category, she pointed out.

“The community was deprived of any legal identity and gradually it faded outside the margins of society. And this shunning by society has resulted in the community withdrawing into itself and living within its own world,” said Sharma.

As a consequence of the tag of criminal tribe, Pardhis were looked upon as lowly and dangerous.

This has only wired the chasm between Pardhis and the rest of the world.

Traditionally, the girls in the Pardhi community are married off at a very young age. “Despite our best efforts the girls are taken out of our hostel by the time they are 12 or 13 years old and married off when they have just studied up to the eighth or ninth grade,” Sharma said. There is pressure on the children to get married and their parents in turn are pressured by their society, she explained.

While that is a cause of regret, Sharma said, those who studied at least till the eighth or ninth, have had some education. “In a community where women are completely uneducated, this is an improvement,” Sharma pointed out.

“A conversation with a few Pardhi people revealed how they still were a target of unfounded suspicion. They felt that only education could narrow the gap between them and the others, and give them equal opportunities and respect,” Sharma said. “The Pardhi community has also placed its trust in Aranyavas and has sent its children to stay here and get that education,” Sharma concluded.

Also Read: Married at 8 and unlettered herself, 49-year-old Saguni Devi from Ajmer champions girls’ education