An eleven-second video I received on my WhatsApp was so soothing. The branches of a mango tree, laden with fruit swayed in the breeze, and the kaccha mangoes danced, occasionally bumping into each other. Watching the sheets of rain in the clip, I could almost smell the fragrant petrichor.

But, something was not quite right. The video was shot three days ago, on May 1, a time when it is peak summer in north India with the mercury often crossing 40 degree Celsius.

‘Never seen such a pleasant May month in Lucknow’ — was the caption that came with the video. I immediately recognised the mango tree which stands tall outside the Gaon Connection office in the City of Nawabs, the capital of Uttar Pradesh. The state is India’s highest mango producing state.

Mango trees love hot and humid climates. I remember, as kids complaining about power cuts in the searing summer heat. But our nanis and dadis would console us saying the hotter the summer, the sweeter the mangoes.

Winter brings little precipitation and snowfall has shifted to April and May months.

But that was several decades ago when weather still followed a familiar pattern; when winter gave way to spring, which slowly transitioned to the summer season. Now the weather is all mixed up! Winter brings little precipitation and snowfall has shifted to April and May months. States such as Uttarakhand and Jammu & Kashmir have a weather alert and are experiencing snowfall now, in May! ‘Rather than a white Christmas, now we have white Holi’ has become a common refrain.

Also Read: As Spring Goes Missing

Pretty as the mango tree WhatsApp video was, it worried me. More so because I had just returned after attending a two-day national workshop on heatwaves organised by Climate Trends. The venue of the workshop was Bengaluru in Karnataka, where election fever is at an all time high.

But, unlike other journalists who have arrived in the Silicon Valley of India to report on the elections, a bunch of environment and climate journalists, like me, travelled to Bengaluru to understand heatwaves (terrestrial and marine), changing monsoon rainfall patterns, warming of the planet and its devastating effects that are already being felt across the globe. And to learn how best we could report on these issues and press for action.

Slide after slide, map after map, climate scientists showed the latest evidence and data of the impact of climate change.

Over two days, climate scientists, academicians, researchers and field practitioners explained the nitty gritty of climate change. There was training on how to report on erratic weather events, heatwaves, teleconnections, monsoon, El Niño – La Niña, and related issues.

Slide after slide, map after map, climate scientists showed the latest evidence and data of the impact of climate change — which poses a direct threat to the livelihoods and economy, health, food basket, water systems, and our very existence.

April and May are usually associated with heatwaves. But this year, several parts of the country have observed below normal temperatures (Mumbai received pre-monsoon showers, which is almost unheard of!). In sharp contrast, heatwaves arrived much earlier, in the beginning of March, damaging crops that were getting ready for harvest.

Also Read: Feeling The Heat

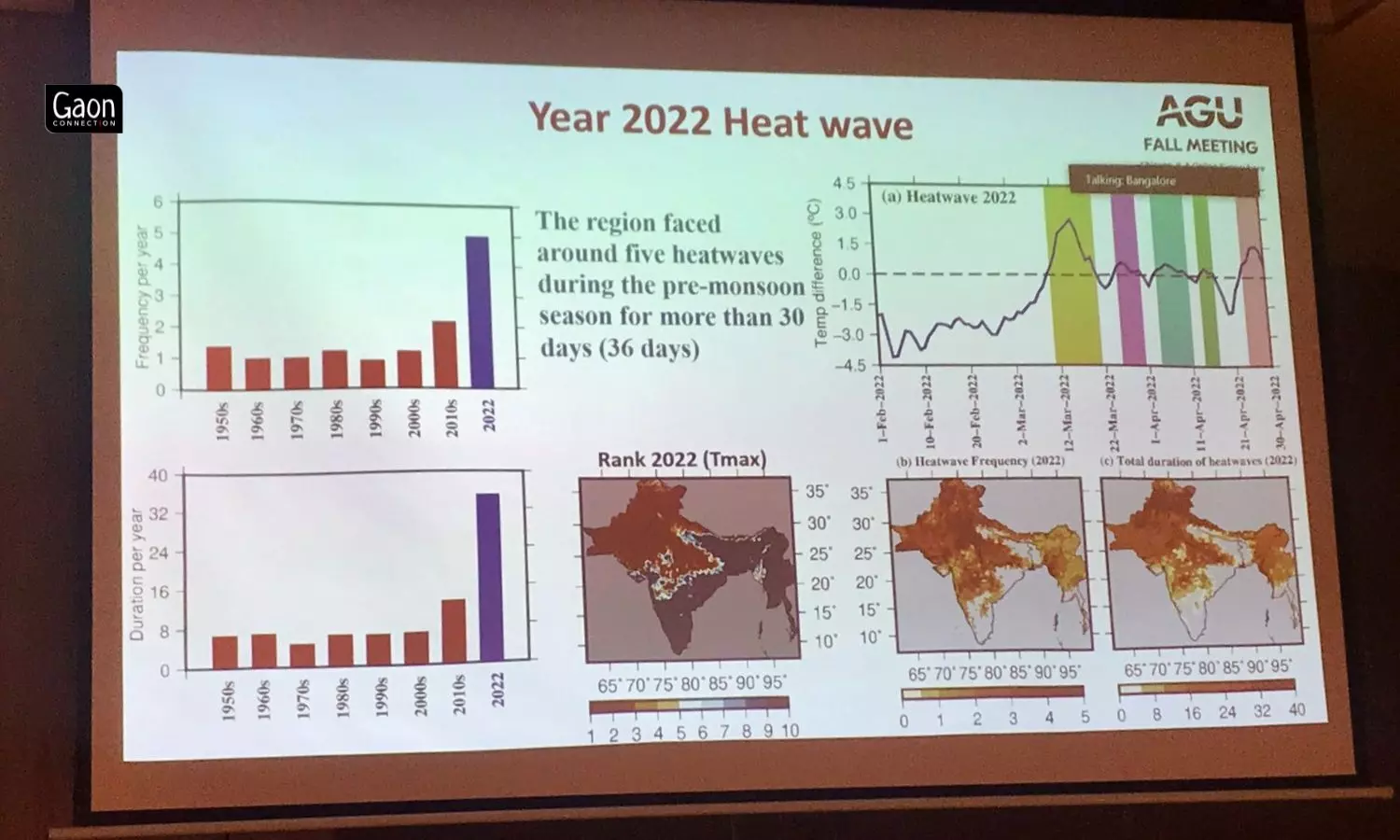

Last year, in 2022, the country faced unprecedented heatwaves, both in terms of intensity and frequency. Vimal Mishra, professor of civil engineering and earth science at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Gandhi Nagar, who has analysed data of heatwaves, presented the findings at the Bengaluru workshop. They were worrying revelations.

The Indian region faced around five heatwaves during the pre-monsoon season last year (February to April) that extended for 36 days. Misra showed how both the intensity and duration of heatwaves have increased sharply. For instance, between the 1950s and 2010s, the duration of heatwaves ranged between seven days and 12-13 days in a year. But, in 2022, it jumped to 36 days (see graphic).

Similarly, the frequency of heatwaves ranged between one and two events per year (1950s to 2010s). But last year, there were five heatwaves in the pre-monsoon season.

The Indian region faced around five heatwaves during the pre-monsoon season last year (February to April) that extended for 36 days.

“The unprecedented heatwave, like the one in 2022, is projected to become very frequent in future warming, which will pose a severe impact on the highly populated Indian subcontinent region,” warned Mishra, stressing on the need to develop and implement district-level heat action plans.

The biggest impact of heatwaves, as pointed out by him, will be borne by the workers and labourers. Gaon Connection has already been recording such stories.

Heatwaves aside, rising temperatures and warming of the oceans is impacting our monsoon, which, for centuries, has irrigated our farmlands, replenished our freshwater sources and sustained all life forms, besides inspiring poets and lovers.

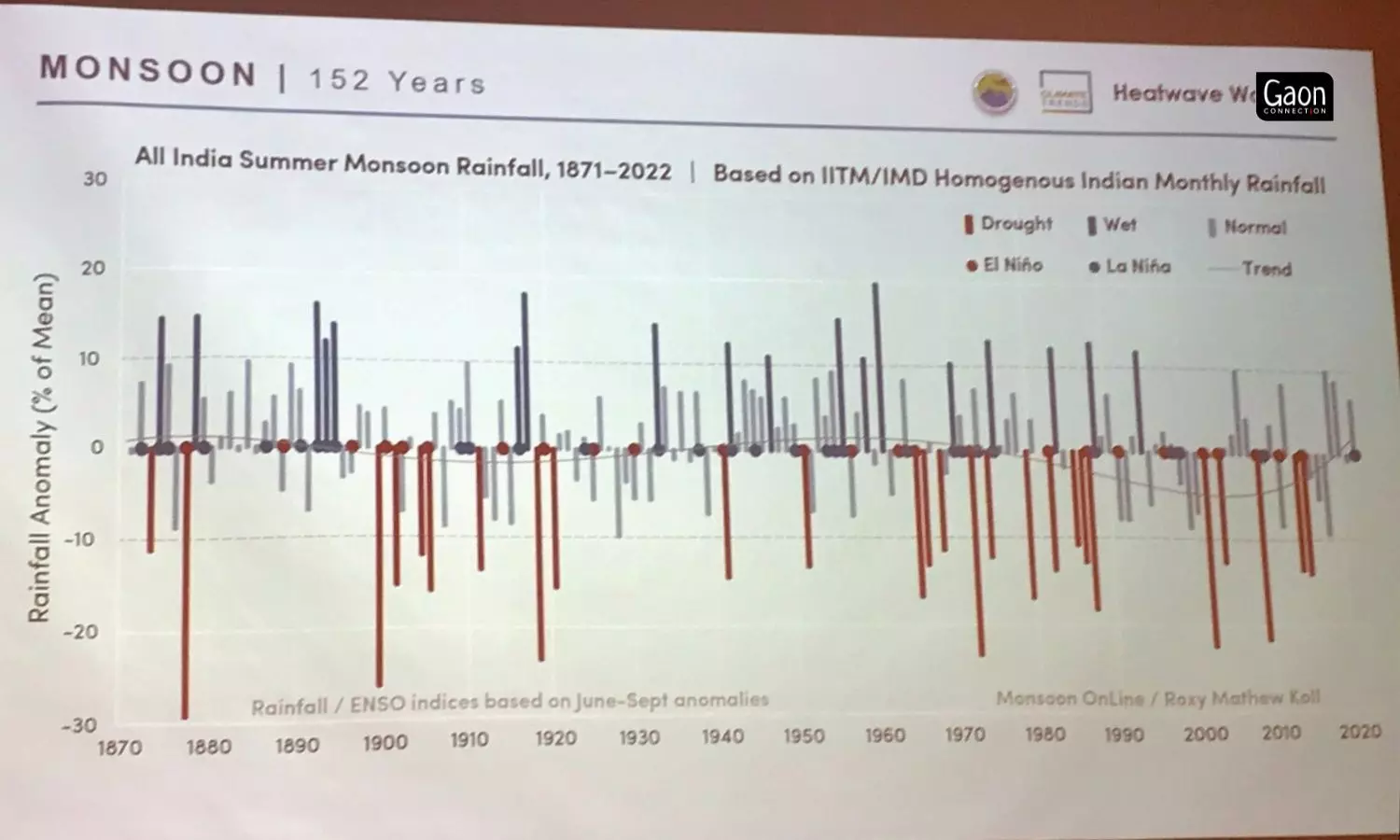

Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, presented the analysis of 152 years of all India Summer Monsoon rainfall, from 1871 to 2022.

The IITM analysis shows that post 2000, there has been no ‘wet’ year (rainfall anomaly of more than 10 per cent of mean) in the country, whereas there have been drought years (see graph). Koll also pointed out that about 50 per cent of drought years are El Niño years.

The IITM analysis shows that post 2000, there has been no ‘wet’ year in the country.

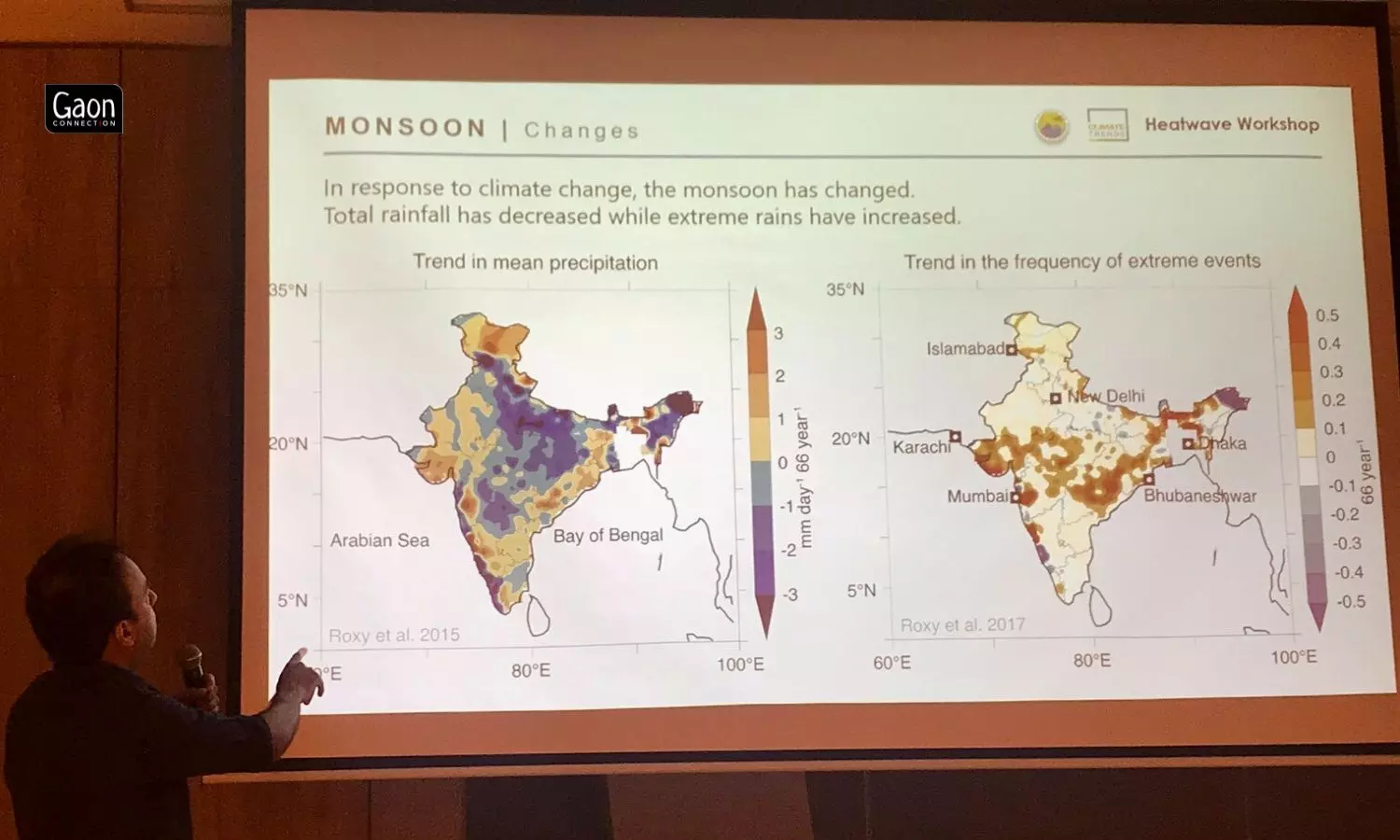

The bad news doesn’t end here. Koll pointed out how in the past 70 years (1950 onwards), there has been a significant reduction in total monsoon rainfall in the Indo-Gangetic basin and central India, and a significant increase in Gujarat and Central Maharashtra. Meanwhile, extreme rainfall events have increased in parts of central India.

In the past 70 years (1950 onwards), there has been a significant reduction in total monsoon rainfall in the Indo-Gangetic basin and central India.

Rainfed agriculture occupies about 51 percent of the country’s net sown area and accounts for nearly 40 per cent of the total food production, as documented by the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare.

To put it simply, erratic monsoon rainfall means our monthly grocery bills will rise and there is a likelihood of increased water stress.

Also Read: Lighting up Nepal’s Future by Marrying its Hydro and Solar Sectors

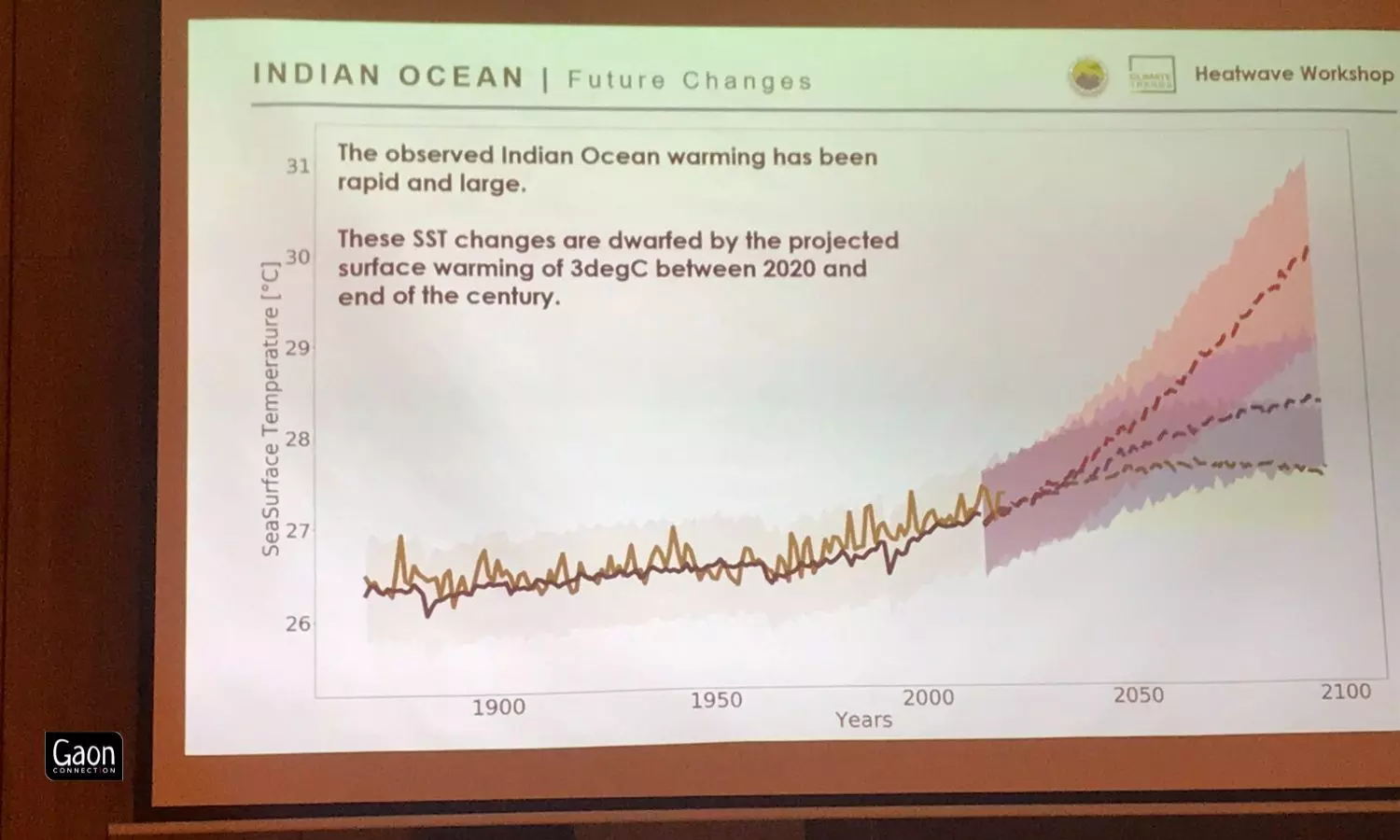

Koll also talked about the Indian Ocean which is the fastest warming ocean in the world. “The observed Indian Ocean warming has been rapid and large,” he said as he presented data analysis which shows that between 1901 and 2013, the sea surface temperature in the Indian Ocean has already increased by 1.2 degree C. It is likely to increase by another 3 degree C between 2020 and 2100!

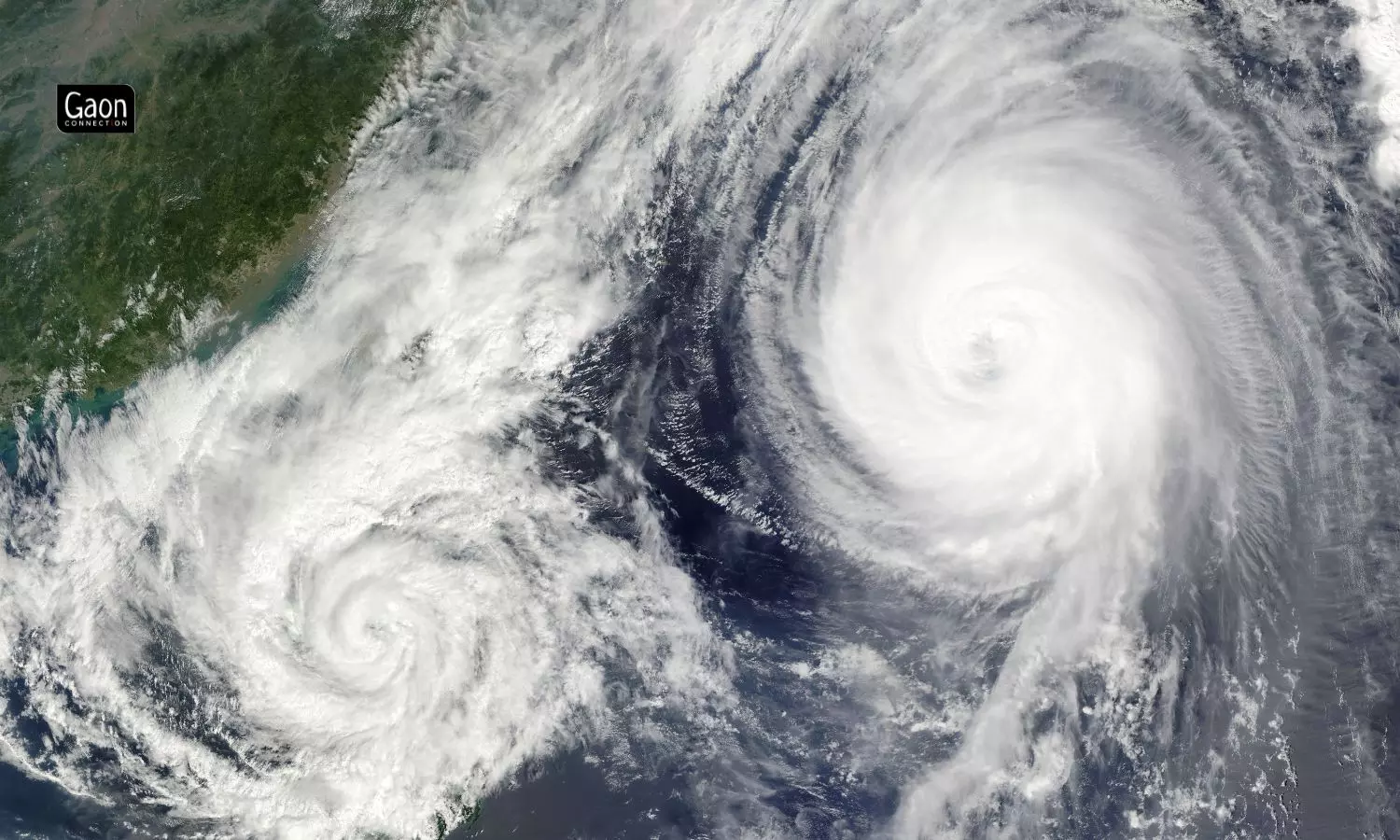

Warming of the ocean is linked to both increased frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones.

This can be catastrophic as warming of the ocean is linked to both increased frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones. The Arabian Sea has been warming at a faster pace and reporting more cyclones, as has been documented by the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

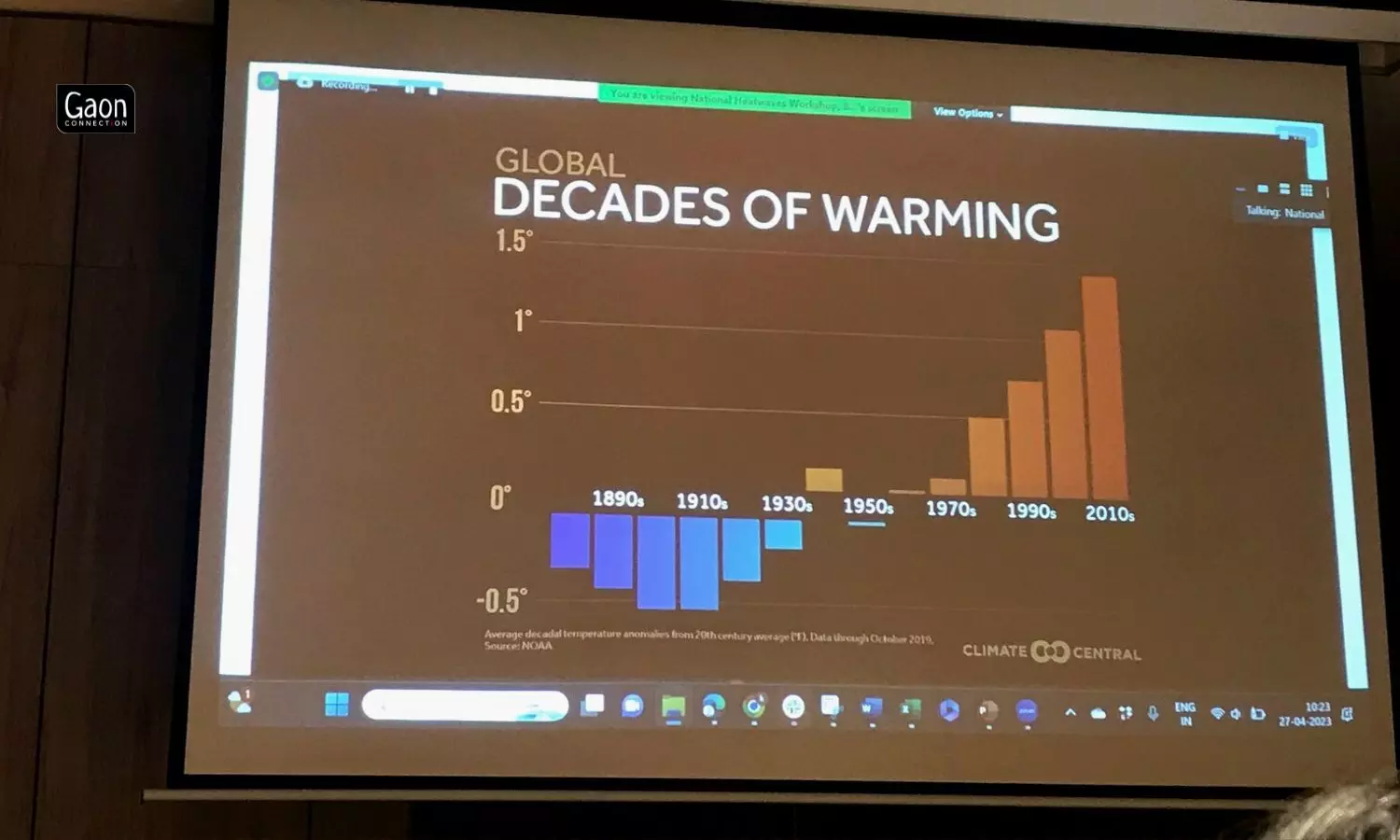

In his detailed presentation, Raghu Murtugudde, an earth system scientist and visiting professor at IIT Bombay, showed how each decade has been warmer than the earlier one (see graph).

Globally each decade has been warmer than the earlier one, pointed out Raghu Murtugudde of IITB.

Murtugudde went on to add that it was meaningless to talk about a normal monsoon as every monsoon was likely to be crazier. “We are getting hammered from Pole to Pole, tropic to tropic… Pre-monsoon rainfall has become erratic and is interacting with heatwaves,” the earth system scientist said. He added that we needed better weather forecasts at granular level and adaptation at local level.

We don’t need to wait till 2070, or even 2050 to experience the devastating impacts of climate change on the lives of common people. Luke Parsons, postdoctoral associate with Duke University, presented some disturbing numbers on annual productivity losses due to the rising heat.

According to him, globally 220 billion hours in a year (in shade) are lost due to the rising heat and wet-bulb temperature. A wet bulb temperature (that takes into consideration both heat and humidity) of 32 degree C is usually the maximum that a human body can endure and carry out normal outdoor activities in.

Of the total 220 billion hours lost, almost half (46 per cent) — 101 billion hours lost — are from India. This is equivalent to about 23 million jobs lost, Parsons said.

Can India afford to lose them?