Parijat Ghosh and Dibyendu Chaudhuri

Smartphones, without any doubt, have become an essential part of our lives to access the internet for communication, entertainment, financial transactions, education, etc.

During the COVID-19 pandemic use of smartphones increased manifold. However, though decreasing, there is still a great divide with respect to region, gender, class, caste, etc. as far as access to mobile networks and ownership of smartphones are concerned.

According to a Times of India report published on December 31, 2022, Telecom Service Providers’ data showed that as of March 2022, out of 644,131 villages in India, around 598,951 (93 per cent) villages had 4G mobile networks.

Also Read: Rich lands and poor Adivasis – how to address this inherent contradiction in tribal areas

PRADAN, a national-level non-profit, came up with their first report on the Status of Adivasi Livelihoods (SAL 2021) in April 2022 covering the states of Jharkhand and Odisha. Further analysis of the data collected for the report shows a grimmer picture of the Adivasi region in terms of access to mobile networks and smartphones. Within the region, Adivasi women are the most disadvantaged.

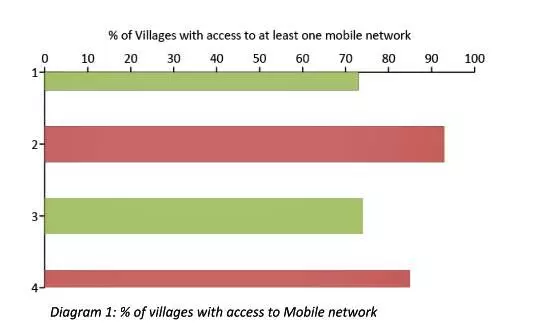

According to the data collected from a sample of 4,994 households from 284 villages of 53 ITDP (Integrated Tribal Development Programme) blocks, the entire Adivasi region in both states shows much lower access to mobile networks than the average national scenario. However, within the region more non-Adivasi villages have access to mobile networks than Adivasi villages.

Nearly 73 per cent of Adivasi villages in Jharkhand and 74 per cent of Adivasi villages in Odisha have access to at least one mobile network as compared to 93 per cent and 85 per cent non-Adivasi villages in both states, respectively.

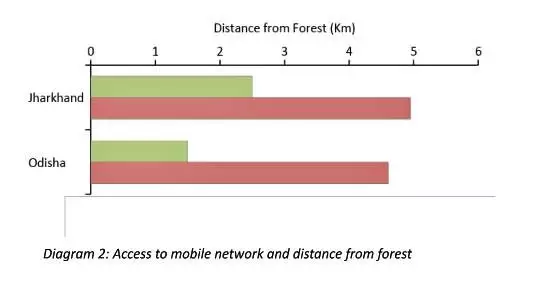

Adivasi villages which do not have access to mobile networks are closer to the forest as compared to those that have access to a network. The average distance of forest from villages having no access to any mobile network is 2.5 kilometres (kms) in the case of Jharkhand and 1.5 kms in the case of Odisha. Villages having access to at least one mobile network are almost 5 kms away (average distance) from the forest in both states.

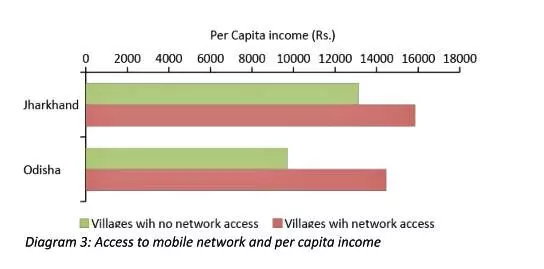

Interestingly, villages which can access a mobile network have more per capita income on average than the villages which do not have access to a mobile network. A deeper study is needed to understand whether access to the mobile network has impacted peoples’ livelihoods or whether the mobile network has been created near villages which are economically better off.

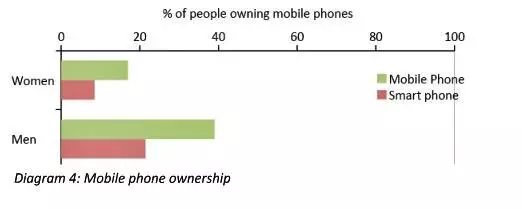

In terms of ownership of mobile and smartphones, only 17 per cent of women own a mobile phone as compared to 39 per cent of men in the area. Almost half of these mobile phones are smartphones.

Access to mobile and networks is not limited to only communication and entertainment anymore. Digitisation has transformed education, workspaces, travel, market access, financial transactions and many other important areas of life. Unless focused attention is given to do away with this divide, it will lead to further marginalisation of the Adivasis, especially Adivasi women.

Ghosh and Chaudhuri work with PRADAN, and were part of the core group that worked for the ‘Status of Adivasi Livelihoods 2021’ report. Views are personal.