Baraipur (Varanasi), Uttar Pradesh

Mira Devi pulled out a few weeds at the base of the bheent so that the shiny green paan leaves can breathe better. The 58-year-old laughed saying that she could do this even blindfolded. “I have been cultivating paan leaves for four decades in Baraipur ever since I came here as a 16-year-old bride,” she said.

There was a tinge of sadness in Mira Devi’s voice as she said she didn’t know how much longer she and her husband will continue to grow the famous Banarasi paan (betel leaf).

Mira Devi is just one of the two paan farmers left in the entire Varanasi district (formerly known as Banaras) of Uttar Pradesh, which is world famous for the Banarasi paan.

For centuries, the Banarasi betel leaf has been the pride of Benaras. And, who does not know the song Khaike Paan Banaras Wala, immortalised by Amitabh Bachchan in the blockbuster Don.

But, the iconic paan Banaras wala is losing its sheen, despite receiving the coveted GI (geographical indication) tag last month on April 3. Farmers, who traditionally grew the Banarasi paan, have switched over to other occupations to make both ends meet.

Also Read: The Fading Fragrance of Desi Betel Leaves in Munger, Bihar

Pointing to her bheent, Mira Devi recalled how they were everywhere one turned in the village. The bheent is a thatched structure, locally made up of bamboo, grass, straw, etc, that is erected in order to support the creeper. The vines of betel leaves wrap themselves around the support as they grow.

“The paan we grew went as far as Mumbai, Delhi, Pratapgarh and other cities of Uttar Pradesh. But now, just to fulfil the needs of our district has become a struggle,” the paan farmer from Bachaav panchayat told Gaon Connection.

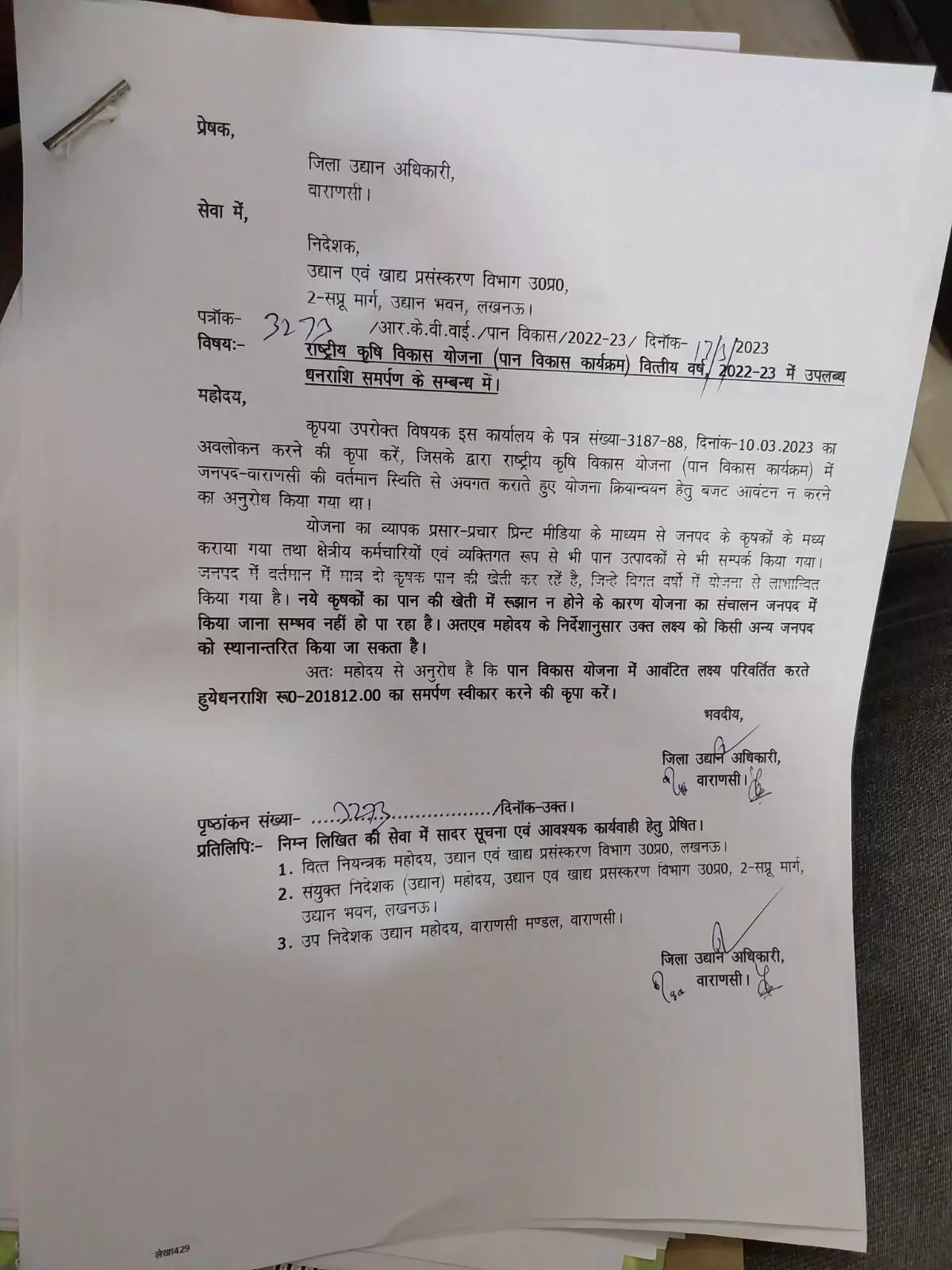

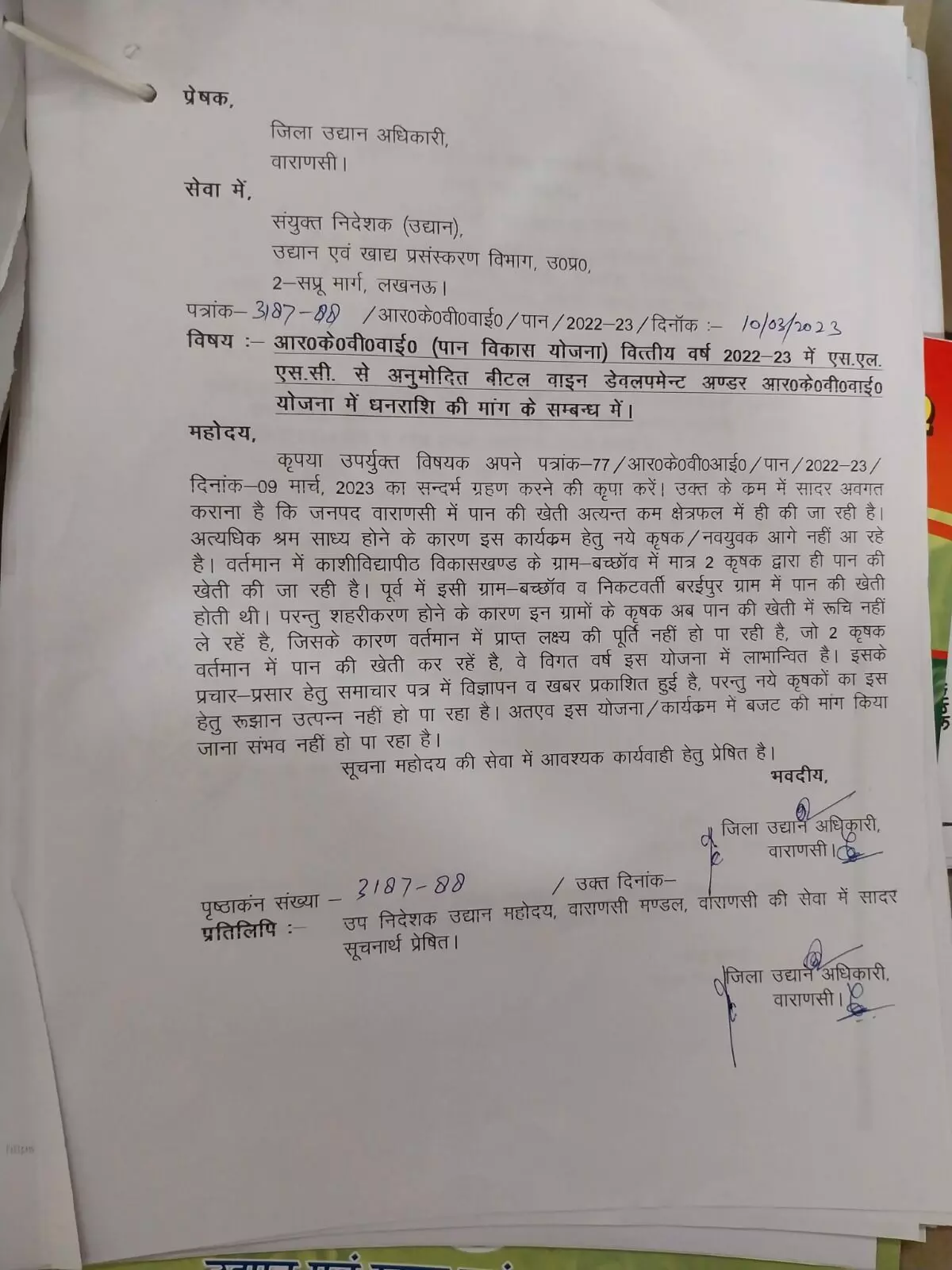

As per official records, only two farmers are left in the entire Varanasi district of Uttar Pradesh, who still cultivate the betel leaf. Gaon Connection has accessed official letters that show that the district horticulture department is unable to utilise the funds meant for the promotion of paan cultivation due to lack of enough betel leaf farmers.

According to a letter dated March 10, 2023 by the district horticulture officer, there were only two betel leaf farmers left in the entire Varanasi district and both were in Bachaav panchayat. Mira Devi is one of them.

Three days later, in another letter addressed to the horticulture department in Lucknow, the district horticulture officer informed that the latter has to return the Rs 201,812 that had been given to the district to promote paan farming in 2022-23.

Faded glory

Paan is considered auspicious in Varanasi. The story goes that the first-ever seed of the paan was planted by Shiva and Parvati at Mount Kailash from where they brought it to Kashi (another name of Varanasi). Since Varanasi is the city of Shiva, it became a part of life in the ancient city.

Folklore also connects Banarasi paan to the Ramayana. It is said that when Hanuman visited Sita in Ashok Vatika and she had nothing to give him, she plucked paan leaves and quickly made a garland of it. Even today paan is offered to Hanuman, especially in Varanasi.

But betel leaf farmers fear that soon the Banarasi paan may remain alive only in folklore as paan cultivation is on a decline.

“There is nothing in it for us anymore,” Rajesh Chaurasiya, a former paan cultivator from Chaurasiya basti in Baraipur village, told Gaon Connection. Till about a decade ago, the village in Bachaav panchayat had 60 or more farmers who cultivated the fragrant Banarasi betel leaf.

As per official records, only two farmers are left in the entire Varanasi district of Uttar Pradesh, who still cultivate the betel leaf.

Also Read: Betel leaf farmers of UP’s Bundelkhand have stories of loss during the lockdown to share

“But now there are just two farmers who continue to grow it. Because of the high cost of growing it and negligible profits after putting in all that hard work, the younger generation sees no point in keeping up with it,” complained Rajesh Chaurasiya.

He gave up on paan cultivation and now works at a grocery store nearby as a labourer, and earns Rs 500 a day as wages.

“My forefathers were paan farmers. But, there is nothing there for me anymore. It is difficult to even get back the investment in growing the crop. We now live off the five hundred rupees a day I earn now,” Rajesh added.

Meera Devi complained about the rising cost of paan cultivation. “It is becoming a struggle to cultivate the paan. The cost of pesticides has gone up and if we suffer crop loss for any reason, there is no help from the government,” she said.

For Manjit Chaurasiya, a former paan farmer from Siwan village, it is still painful to talk about paan cultivation.

“I cultivated paan on my three bighas of land in Siwan. But my bheent caught fire and I lost everything. I had borrowed money from others in my village and invested about seven lakh rupees on the cultivation,” Manjit told Gaon Connection.

Manjit never could recover from the loss and he sold his land, settled some of his debts, and is trying to repay the rest. “My mother fell ill after the disaster and she has still not recovered,” Manjit said.

Need government support

Varanasi is also a collection point for betel leaves that come from other parts of the country, such as Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. And once they get here they are all clubbed under the label of ‘Banarasi paan’, complain the local farmers.

“But, there is something special about the Banarasi paan that no other paan, anywhere else in the world, has. It is the way the harvested betel leaves are seasoned that gives them that distinct fragrance and flavour,” Santosh Tiwari, a well known journalist from Varanasi, told Gaon Connection.

“The process of curing the betel leaf is an art that is also a closely guarded secret. Betel leaves that are grown anywhere elsewhere in the country will never have that texture and aroma,” he said.

Mira Devi is just one of the two paan farmers left in the entire Varanasi district (formerly known as Banaras) of Uttar Pradesh, which is world famous for the Banarasi paan.

Also Read: The betelnut handicraft of Rewa

Government officials are promising support to the farmers. “All support will be extended from the horticulture department to the paan farmers,” Jyoti Kumar Singh, officer at the Horticulture Department, Varanasi, told Gaon Connection. “Farmers will get grants according to the size of their land. Once a farmer is given this grant, he or she can apply for another one only after three years,” Singh said.

The horticulture officer went on to inform that the GI tag also includes betel leaves that are grown in Mirzapur, Ghazipur and Jaunpur.

“After the GI tag, we have roped in an agency to survey the present scenario in Banarasi paan cultivation, and come up with ways to bring the former paan farmers back into the fold,” he said. This will include offering subsidies, grants, easy loans and support that may want them to get back to their traditional occupation of cultivating the Banarasi paan.

“We are waiting for directions from the government and once we get that, we will hold awareness drives and camps to give paan cultivation a shot in the arm,” the officer added.