For those who feel assimilated to nature, amidst woods, grasses, plants, leaves and petals, How I Became A Tree penned by Sumana Roy, would be an engrossing read. I came across a dwelling of the author’s thought, which she called ‘Silence of Tree’, whose few lines resonate with me, “I need to say it again, among all other desires to become a tree, the most urgent was the need to escape noise. There were two things about this, one was the noise of humans, the other was the vocabulary of silence of the active life of trees.”

I sense that this vocabulary of silence of trees may change, with time, conditions, and events around. It would be different sets of words used by native and ‘exotic’ trees.

Sometimes, I also sense — trees which have willingly or unwillingly migrated to a foreign land, across the seas, several thousands of miles away from their home — have a different vocabulary from the one back home likely stemming from their isolation, grief, happiness, destitute, loneliness, friendships, or adoptions.

Speaking to a tree which is native and one which is a migrant yields distinct understandings. I hear from the tales of the trees, their inhibitions, their laments, their needs. The ones labelled ‘exotics’ more so; the word itself stamping them as second-grade — refugees or migrants.

They bear these labels for years, even centuries, alienated, separated, discriminated – until the point that they either adopt themselves to their new home, or get camouflaged in its stories, mythology, religions, conversations, or living.

Also Read: The Saga of the Scarlet Semal

The best example of such a tree is Gulmohar (Delonix regia), a Madagascar-native that came to India years ago. Found in many places around the globe, the tree has adopted splendidly.

It has inhabited so well that Indians consider it a native tree, its intrinsic assimilation into our society is seen in Dushyant Kumar’s sher – jeeye toh apne bageeche mein gulmohar ke tale, marein toh gaer ki galiyon mein gulhomar ke liye. With the onset of time, Gulmohar has garnered acceptance and made itself one with its new home.

Trees are seen through different lenses by different people. In most cases, the acceptance of these non-native trees in society is catalysed by the new local names given to them. One such tree is Balam Kheera, whose name insinuates a native bearing, whereas Kijalia africana actually belongs to Africa. Its local name is derived from the shape of its fruit which strongly resembles a kheera, or cucumber.

Balam Kheera’s local name is derived from the shape of its fruit which strongly resembles a kheera, or cucumber.

It is a beautiful tree with thick foliage, a prominent crown, and thick, leathery, broad leaves in a dark green colour. Balam Kheera has high adaptability and it has even found medicinal use locally. Besides the fruit, another one of its special characteristics is its hanging efflorescence – red, thick, big tubular flowers. It has been planted in avenues, and is found very commonly in cities, such as Delhi.

Gulmohar and Balam Kheera have been absorbed with the native flora because for them, propagation has not been challenging. They have multiplied and claimed spaces, so there isn’t much of a feeling of seclusion, or isolation, or destitution, or stress that they find themselves dealing with.

Also Read: As Spring Goes Missing

But there are some, which do seem affected by these emotions – such as the Kamandal (Crescentia cujete) tree. A Latin-American tree, whose fruits are used for making pots and bowls, derived its name from its use for making Kamandals or ‘begging bowls’.

However, only a few Kamandal trees are found (two or three in Delhi) and they too remain unrecognised unless their brownish flowers start protruding on their trunks and convert into ball-like green fruits. Since they are bat-pollinated, it is interesting that they converse with indigenous bats to help with pollination.

Then there are a few trees that are so quiet and so hidden that they barely seem to be around. Their vocabulary gives off the feeling of hesitation. Such is the Nettle tree (Celtis australis or Khadak in Hindi, which is an interesting name). An original of the Mediterranean and Southern Europe region, it seems to have travelled with Alexander the Great on his journey to India, or somehow wound up on the Silk Route through that way.

Latin-American tree, whose fruits are used for making pots and bowls, derived its name from its use for making Kamandals or ‘begging bowls’.

An interesting feature in the tree is the fall of its bipinnate branches which seem to be almost climber-like, with a clean, slatey, smooth bark. Now, it blends into its surrounding vegetation, like a tree that belongs in the subtropical, dry deciduous, mixed forests. It mingles with subtropical trees as if with the intention of not revealing its identity amongst them. However, Nettle seems to be enjoying its own solitude with swinging leaves in a canopy with hues of green.

A tree that warrants attention is Agathis (Agathis australis), an evergreen tree with an interesting bark – spotted and slatey-brown, which stands out from its habitat. Its thick leaves turn scaly upon drying and it has sustained with elegance on Indian soil. Its distinct straight bowled nature is native to Australia and New Zealand, like Eucalyptus, where it is also known as the Kauri tree.

Kauri forests are among some of the oldest in the world, it has been estimated that the antecedents of the Kauri appeared during the Jurassic period, between 190 and 135 million years ago. It appears that Agathis trees may have wound up in Europe and then somehow found their way to India. The robust, gregariously leafed presence of this tree makes itself known wherever it stands. Extroverted, it seems not only ready to adopt itself to different conditions, but also thrives in them.

Also Read: The Tale of a Striped Monk

We also find Baobab (Adansonia digitata), an African tree which has many names such as inverted tree or bottle tree, and is quite popular and recognised worldwide. It is important for this habitat too, for its ability to store water in its hollowed-out huge trunk when dried and heights reaching many tens of feet. The genetic variance study done of the Indian species of the tree indicates that it is not native and has come from the African region which is its place of origin, however, very interestingly it is called the Kalpavriksha – the tree of life, in India.

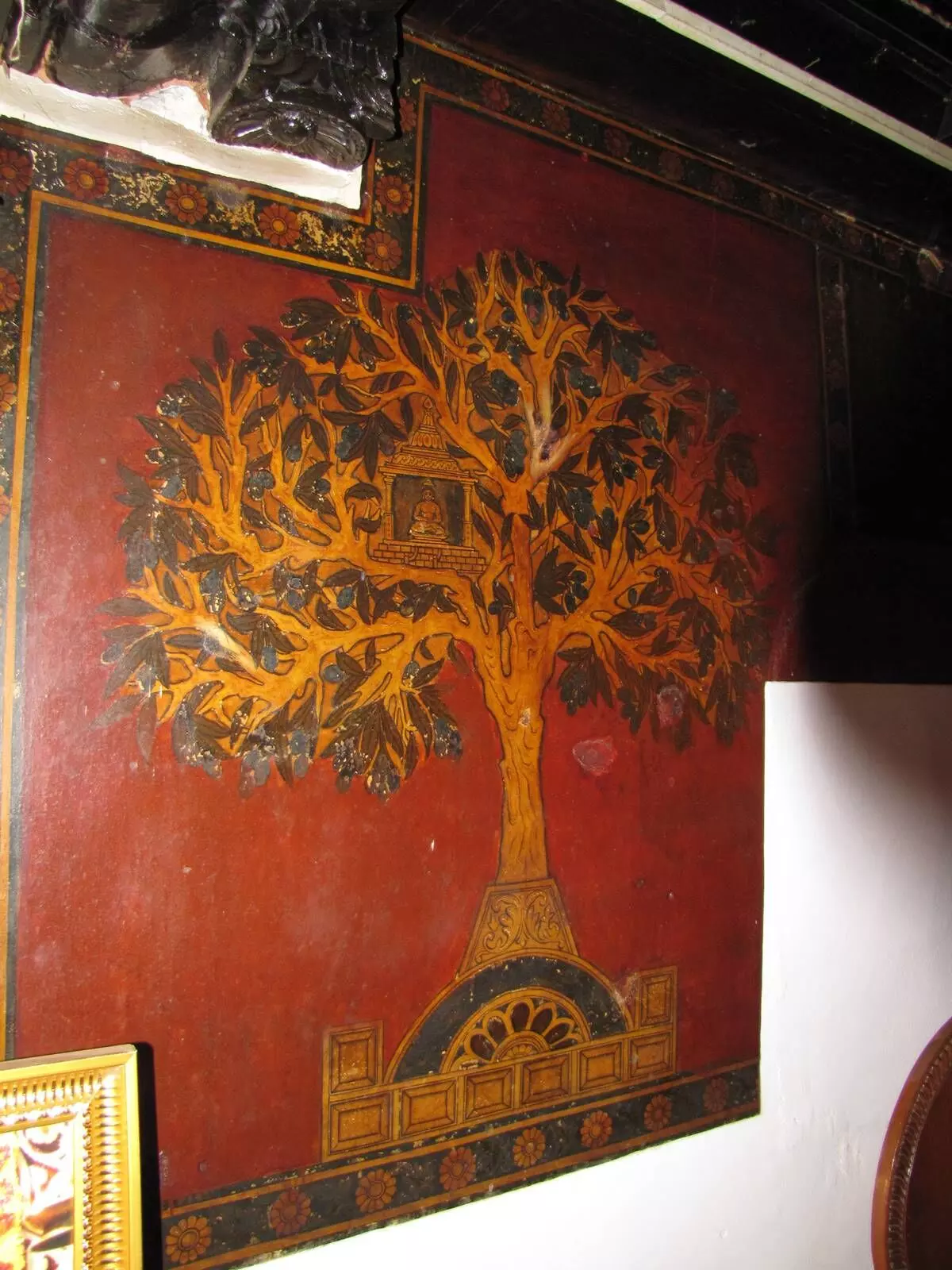

Kalpavriksha is a prominent mythological tree which features in Puranic literature, having appeared from the Samudra Manthan (churning of the ocean by the Gods and Demons) and it has come to be considered auspicious over time. The twist in the tale of Baobab comes when, in certain places such as some parts of Uttar Pradesh, it is also called and revered as Parijat, which is actually a misnomer. This is where the interesting identity of the tree and its recognition come into place.

Kalpavriksha is a prominent mythological tree which features in Puranic literature, having appeared from the Samudra Manthan (churning of the ocean by the Gods and Demons) and it has come to be considered auspicious over time.

Parijat, commonly known as Harshringar, Shiuli or Shefali in India, is an indigenous tree that features in the Puranas, Sanskrit literature and Krishna’s tales. Absolutely different from this tree which flowers in ample in October, Baobab is found quite sporadically in India with a few pockets in North, West and South India with at most one or two trees in one place.

Baobab trees look like Semal trees in their morphological appearance and feel, and speculations have been made regarding them coming to India either with the Arabs or the Portuguese who planted them near churches in many parts of Western India. The Kalpvriksh has been worshipped in its newfound identity for many years, especially in North India. Baobab has adapted well to the native soil and its seedlings can be raised in nurseries, its mushroom-like white flowers look beautiful when they fall and cover the ground beneath the tree.

In today’s world, the cross-generational knowledge of trees is not being passed down, there is a greater need to observe, identify, recognise, and appreciate trees. We are all familiar with the Company Baghs or Gardens established in many cities by the East India Company, which are frequented by joggers and morning walkers today. Some of them subsequently became the regional offices of the Botanical Survey of India (such as in Saharanpur, Allahabad, and Calcutta), with the objective of putting exotic and native trees in one place, knowing about them, their phenology, behaviour, and propagation.

This spirit of connecting with trees and delving into their Vocabulary of Silence needs to go on, we need to encourage inquisitiveness about trees and their origin, their better use, and inculcate communication with them, their journeys, and their stories, in their words.

Ramesh Pandey is an Indian Forest Service Officer who is currently serving as the Inspector General of Forests in MoEFCC, GoI at New Delhi. He has been awarded the UNEP Asia Environmental Enforcement Award. Views expressed are personal.