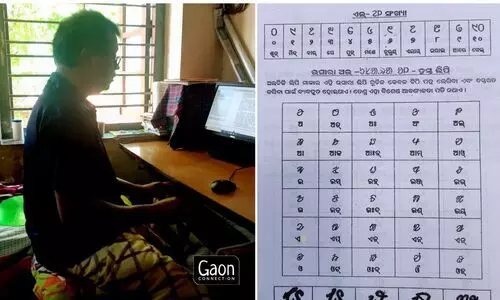

Biswanath Tudu, an employee of Life Insurance Company of India (LIC) at Rourkela in Odisha, is also a prolific writer. He has 104 works to his name that include novels, travelogues, poems, children’s stories and collections of proverbs.

What sets the Santhal’s work apart is the fact that all his writings are in Ol Chiki, which is a unique script developed for the Santhali language of the Santhal tribal community spread in Jharkhand, West Bengal and parts of Odisha. It is estimated that over seven million people speak the Santhali language in India.

Tudu is the first writer to win the Bal Sahitya Puraskar instituted by the Sahitya Akademi in 2010 for his writing in Ol Chiki. It was his compilation of 15 children’s stories called Sishu Saoned, which he wrote in Ol Chiki script in 2004, that earned him the prestigious award.

The Ol Chiki script, also known as Ol Chemetʼ, Ol Ciki, Ol, and sometimes as the Santhali alphabet, is the official writing system for Santhali language, which is recognised as an official regional language in India.

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santhali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official languages of India. This addition meant that the Indian government was obligated to undertake the development of the Santhali language and to allow students appearing for school-level examinations and entrance examinations for public service jobs to use the language.

Also Read: A teacher’s crusade to make sign language the 23rd official language of India

And all this would not have been possible without Pandit Raghunath Murmu of Mayurbhanj in Odisha who for the first time introduced the script, Ol Chiki, to the world in 1925.

Tudu also belongs to Mayurbhanj and originally belongs to Andharjur village but has been living and working in Rourkela with LIC. And his journey as an Ol Chiki writer is full of struggles. Despite his day job as an employee in LIC, he remains committed to promoting Ol Chiki script and Santhali language.

In 2003, the 92nd Constitutional Amendment Act added Santhali to Schedule VIII to the Constitution of India, which lists the official languages of India.

Tudu’s first novel was the sombre Haire Chando Likhon that he wrote in 1987. “In it the protagonist is faced with a series of tragedies. She lost her father in childhood, lost her mother to domestic violence and a childhood friend to an accident,” he told Gaon Connection. “Though I wrote it in 1987, I had no money to publish it and could only do so in 2003, a decade after I joined LIC,” he smiled.

But, in 2002, he wrote another novel in Ol Chiki called Bono Amge Injij Hopon (Bono, You Are My Son) followed by his first work for children Sishu Saoned (children’s literature) in 2004.

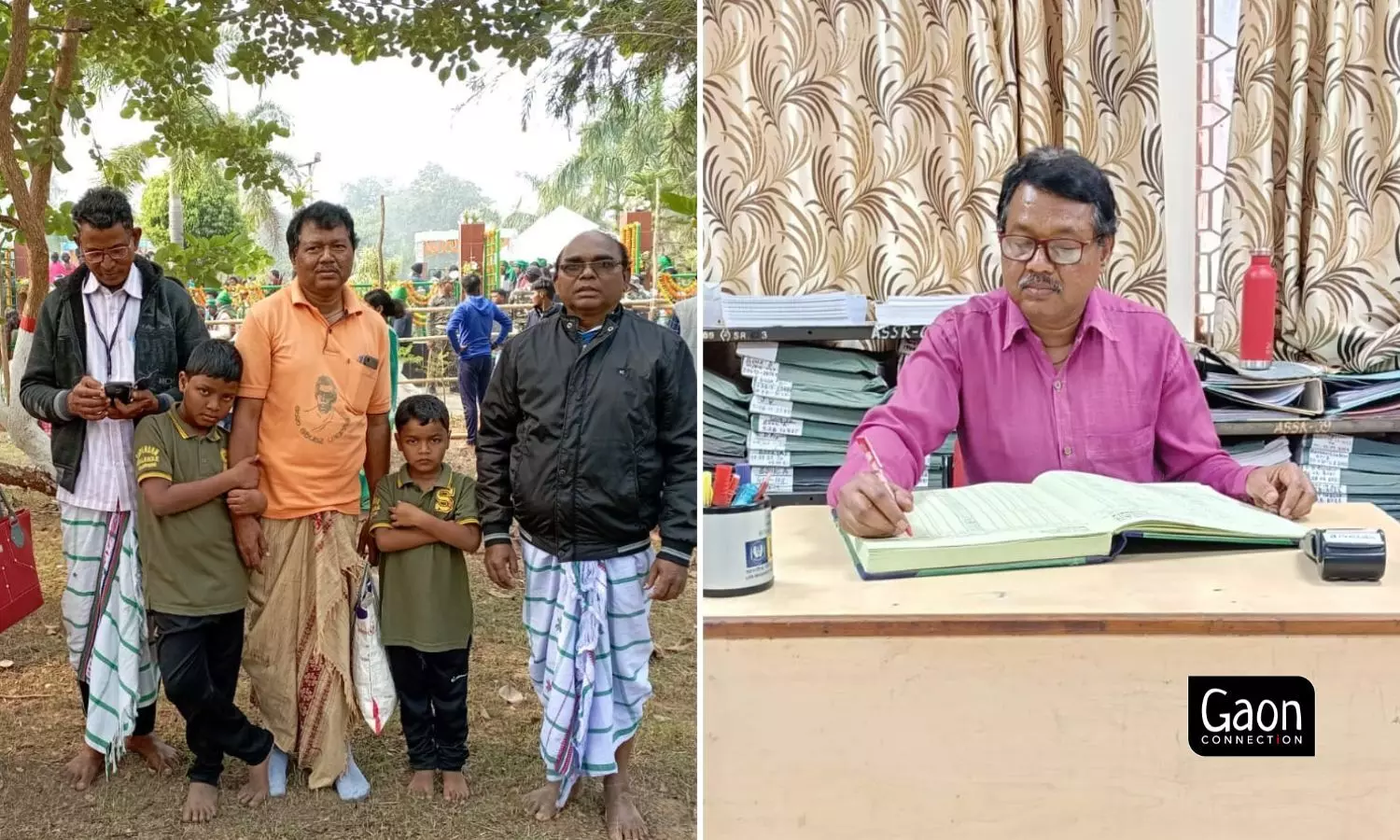

Tudu’s work has greatly benefited Ol Chiki script and Santhali language. “In 2010 when Biswanath Tudu got Akademi Award, there were less than 100 Ol Chiki litterateurs in Odisha who read and wrote Ol Chiki, but now their number has increased to over 300,” Madan Mohan Soren, former convener of the Akademi’s Santhali Advisory Board, told Gaon Connection.

Despite the acclaim he has received in literary circles, Tudu has had to self publish and sell his books himself.

He told Gaon Connection how he managed to sell some of his works to the Harekrushna Mahatab State Library, library of Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences, both in Bhubaneswar, and the National Library, in Kolkata.

“When I toured Jordan, Egypt and Palestine in 2016, I left behind some books at every place of prayer I visited. In 2018, when I visited Jerusalem, I left some copies in a washroom,” said Tudu. “It is very very difficult to find readers in this age of smartphones,” he rued.

Also Read: For the Love of Art and Nanpur Village

“Almost all Ol Chiki authors do so. Though over 300 people in Odisha and over 6,000 in Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Assam, Tripura and Mizoram can read and write the script, only few read literature in the language,” said Arjun Marandi, secretary of Santhali Writers’ Association, Baripada, Odisha.

Marandi felt that government intervention would go a long way in promoting Santhali literature. “If the government prescribed children’s books of noted Santhali writers for primary schools where education is imparted in 21 tribal languages in 17 out of the 30 tribal districts under the Multilingual Education programme, it could boost Santhali literature,” he said.

Despite his day job as an employee in LIC, Biswanath Tudu remains committed to promoting Ol Chiki script and Santhali language.

Odisha is a multilingual state having more than 40 ethnic languages. In 2005, the state government launched a Multilingual Education (MLE) programme to teach 10 tribal languages at MLE schools.

“Santhali is taught in about 457 MLE schools out of over 700 in Santhali dominated Mayurbhanj. In other schools, tribal languages like Ho and Mundari are taught. A tribal language along with Odia is taught up to class two. Then English is added from class three,” Sapan Prusty, tribal coordinator in the Education Department in Mayurbhanj, told Gaon Connection. “At present, just the languages and not literature is taught in MLE schools,” he added.

Tudu said that his two sons, studying in class four and two respectively, can speak Santhali but cannot read Ol Chiki. “ But they will definitely learn it in future,” the writer said firmly.

Meanwhile, only Ol Chiki has found a place in the Indian Constitution’s Eighth Schedule. Other tribal language scripts such as the Warang Citi of Hos, Mundari Bani of Mundas, Ol Onal of Bhumijas, Soreng Sompeng of Soaras Kurukh Bana/Tolong Siki of Oraons, and Kui Lipi of Kondhs were developed.

“But these scripts of other tribal languages spoken in Odisha are still awaiting their inclusion,” Mahendra Mishra, the director of Folklore Foundation, Bhubaneswar, told Gaon Connection. Mishra, a member of Kendriya Sahitya Akademi’s Language Development Board, and has worked on tribal languages for 20 years.