Barabanki, Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh)

As Rajrani weeded her fields in the peak of summers in June, she began to feel unwell. She did not know it then, but the temperature hovered around 43 degrees Celsius. Still, she continued to pull out the weeds, but as she stood up, a wave of dizziness hit her and she fainted. The 35-year-old lay there till her husband found her and rushed her to the hospital.

“I feel dizzy all the time. It is difficult working in the heat, but we have to otherwise how do we earn a living,” Rajrani, a resident of Hemi village, in Lucknow district, Uttar Pradesh, told Gaon Connection.

Watch video

About three kilometres away from Rajrani’s village, 50-year-old Ramkali from Dariyapur village also struggled in the heat. A daily-wge labourer, Rajrani has to work between eight in the morning till noon, when she does digging for a pond that is being constructed in her village.

There is no shade where she works, Ramkali told Gaon Connection. “I feel feverish, dizzy and my eyes hurt in the heat, but labourers like me cannot stop work because of that. If we do, our wages will stop,” said the labourer who earns Rs 213 a day if she works.

Rising heat and the prolonged heatwaves are affecting productivity of rural Indians. This year, heatwaves arrived early in March and the number of hotter-than-usual days have increased, too.

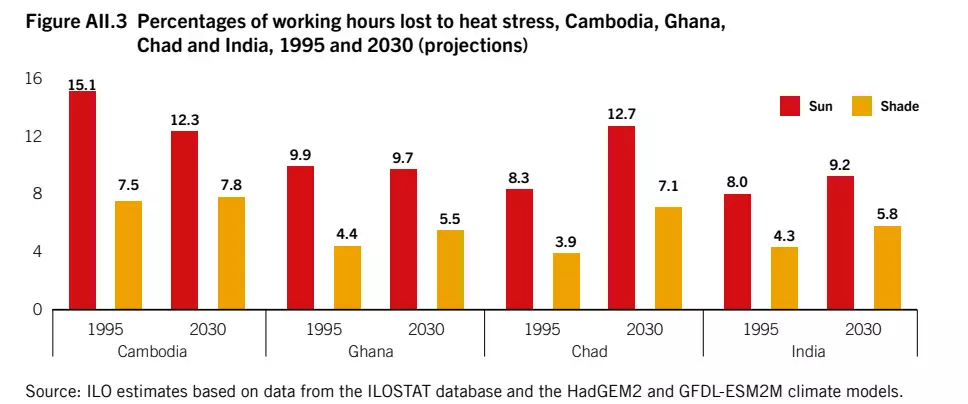

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has warned of the impact of the rising heat. ILO’s 2019 report titled Working on a Warmer Planet – The Impact of Heat Stress on Labour Productivity and Decent Work, warns that India is expected to lose 5.8 per cent of working hours in 2030 due to heat stress. Because of its large population, India, in absolute terms, is expected to lose the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs in 2030 due to heat stress.

“India is going to lose 34 million jobs by 2030 only because of heat waves. Agricultural productivity is going to reduce. It will have some dent on food security, supply cold chain, and the economic sector,” Abinash Mohanty, Programme Lead (Risks & Adaptation) with New Delhi-based research think-tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), told Gaon Connection. “Livelihoods are going to be lost because of the heatwave and the quality of life is going to be impacted,” he added.

Mohanty pointed out that urban areas have better adaptive capacity compared to rural areas: “People in villages do not have access to air conditioners, water coolers or fans,” he said. It is not just an economic impact people will face, but also health implications, besides employment, growth and sustainability issues, he warned.

Rising heat and power cuts in villages

The efficiency and output of work suffers in the summers. Rajrani’s husband was unable to go to work for an entire week as he fell ill due to the heat and that meant a loss of about Rs 2,000 for the poor household.

The heat at night prevents the rural inhabitants from getting adequate sleep, and extended power cuts are making things worse.

Sitting on a charpoy outside her house in Hemi village, 50-year-old Jangrani fanned herself with a bena (hand held fan). “We spend the entire night like this. We cannot get proper sleep,” she complained. While the early mornings were cooler, the people have to get their day started early in order to complete their household chores before they head out.

The rising heat has affected her earnings and productivity, said Jangrani. Photo: Shivani Gupta

A 2022 study by One Earth titled Rising temperatures erode human sleep globally across 68 countries revealed that warmer temperatures reduce sleep globally. The elderly, women, and residents of lower-income countries are impacted most. By 2099, suboptimal temperatures may erode 50–58 hours of sleep per person-year.

“I work slowly and keep resting in between. I feel breathless and often black out,” Jangrani told Gaon Connection, who doesn’t have an electricity connection at her home. Being a small farmer, she manages to earn Rs 200-300 only every third day when she harvests and sells vegetables from her one bigha (0.619 acre, or 0.25 hectare) land. The rising heat has affected her earnings and productivity, the widow said.

Recently, the Uttar Pradesh government assured to provide power for 15 hours a day in rural areas. When Gaon Connection visited several villages in Lucknow and Barabanki districts, villagers complained that power supply was available for barely seven hours in 24 hours of the day.

Desperate mothers apply wet mud on the bodies of their children to keep them cool. “What else do we do? Our children have prickly skin and feel sick,” 30-year-old Hina, a resident of Dinpanah village in Barabanki district, lashed out.

Village kids have prickly skin due to rising heat. Photo: Mohammad Salman

“Power was cut at two in the night and has not come till now (4 pm). We have power for about two hours in the evening. Then from midnight to about five in the morning, after which the supply is cut once again,” 60-year-old Gimla Devi, a resident of Dinpanah, told Gaon Connection.

Early and prolonged heatwaves

According to the India Meteorological Department, the number of heatwave days in India have increased from 413 in the period between 1981 and 1990 to 600 from 2011 to 2020. The increasing influence of climate change has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of heatwave days.

This year the early arrival of heatwaves has also wrought considerable damage to crops such as wheat, mango, litchi, tomatoes, etc. “Our wheat production has decreased this year. In one bigha land, which would get us upto nine katta wheat, this year, we managed to get only four katta,” Rajrani said. [1 katta = 50 kilos]

The heat prevents the rural inhabitants from getting adequate sleep, and extended power cuts are making things worse. Photo: Mohammad Salman

According to Parag Talankar, director of planning and mobilisation wing at SEEDS India, a New Delhi based non-profit that works on disasters and helps build resilience in rural communities, “It is not just health issues, but heatwaves also cause economic cost to daily wagers like construction workers, rickshaw wallahs, vegetable vendors. They are often forced to miss work and have to spend more on medicines,” he pointed out.

Impact on the GDP

A 2021 report titled The costs of climate change in India published by the think tank of Overseas Development Institute (ODI) mentioned that if the average global temperature rises by one degree Celsius, the resulting decline in agricultural productivity, rise in sea levels, and negative health outcomes are projected to cost India about three per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP). It also noted that India’s GDP would currently be around 25 per cent higher were it not for the current costs of global warming.

An average loss in daylight working hours could put between 2.5 per cent and 4.5 per cent of the GDP at risk annually by 2030. This would be equivalent to roughly $150-250 billion. If the situation continues to deteriorate, there will be Rs 52,420 million per day loss of GDP in India, while the hourly loss will be Rs 2.2 million by 2030, the report warned.

As of 2017, heat-exposed work produces about 50 per cent of GDP, drives about 30 per cent of GDP growth, and employs about 75 per cent of the labour force, some 380 million people in India, notes the 2020 McKinsey report.

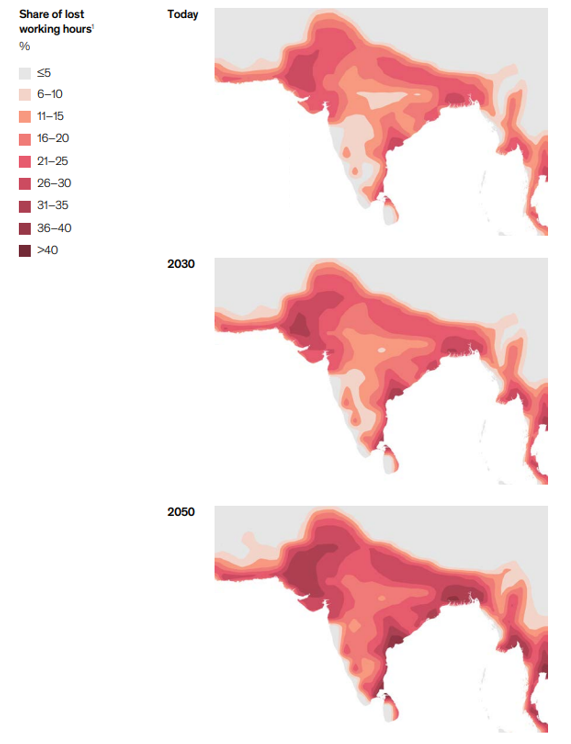

The affected area and intensity of extreme heat and humidity is projected to increase, leading to a higher expected share of lost working hours in India and surrounding areas. Source: McKinsey report

According to the 2019 ILO report 9.04 per cent of working hours are expected to be lost in agriculture and construction sectors, respectively, due to heat stress in 2030.

Rising heat-related illnesses in rural India

Twenty-year-old Anjali is seven months pregnant. She had diarrhoea for three days, and had to be administered an intravenous drip to stabilise her condition.

The resident of Gangepur village in Barabanki told Gaon Connection that she spent a large portion of her day in the kitchen where she cooks food on a chulha using firewood. “It is difficult, and the heat becomes unbearable,” Anjali said.

Anjali had diarrhoea for three days, and had to be administered an intravenous drip. She had to go out (in the open) for defecation at least thirteen times in one day. Photo: Mohammad Salman

Ashish Kumar Singh, a pharmacist working in the Ghunghter community health centre, Barabanki, told Gaon Connection, that there were many cases of dehydration in the summers. “Weakness, sleep deprivation, high pulse rate, and muscle pain are common,” he added.

According to Praveen, another medical officer from Ghughter, dehydration cases increase from mid April till July. “We get at least two to three cases of heat related illness daily. Dermatitis, fungal infection, chickenpox, measles and viral infection cases also increase in the summers,” he said.

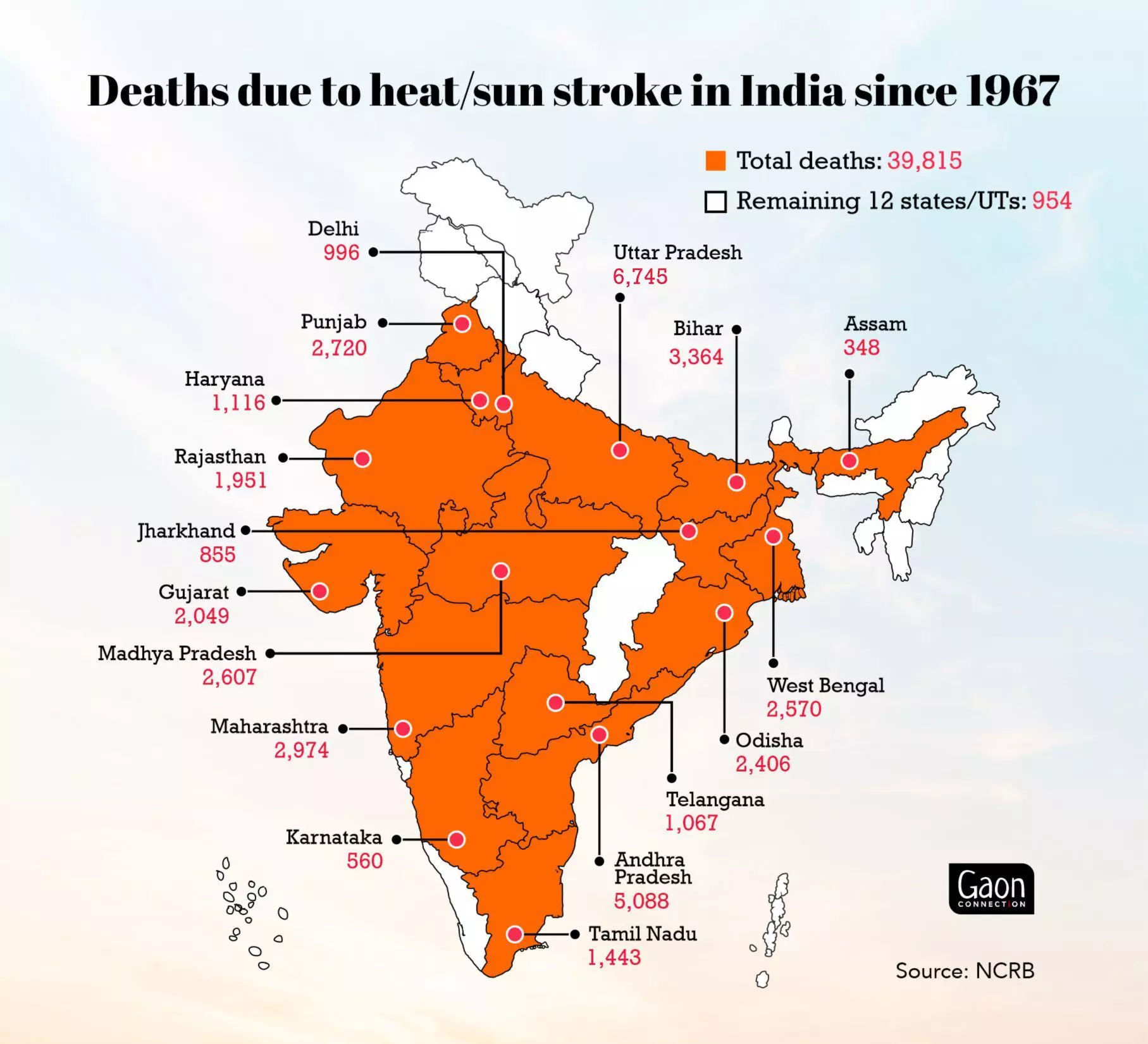

Heatstroke deaths highest in UP

Heat waves have claimed the lives of 39,815 people in the last 50 years since 1967, as per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. Based on the geo-climatic and socio-economic conditions, the highest number of people — 6,745 — have been killed in Uttar Pradesh in these five decades.

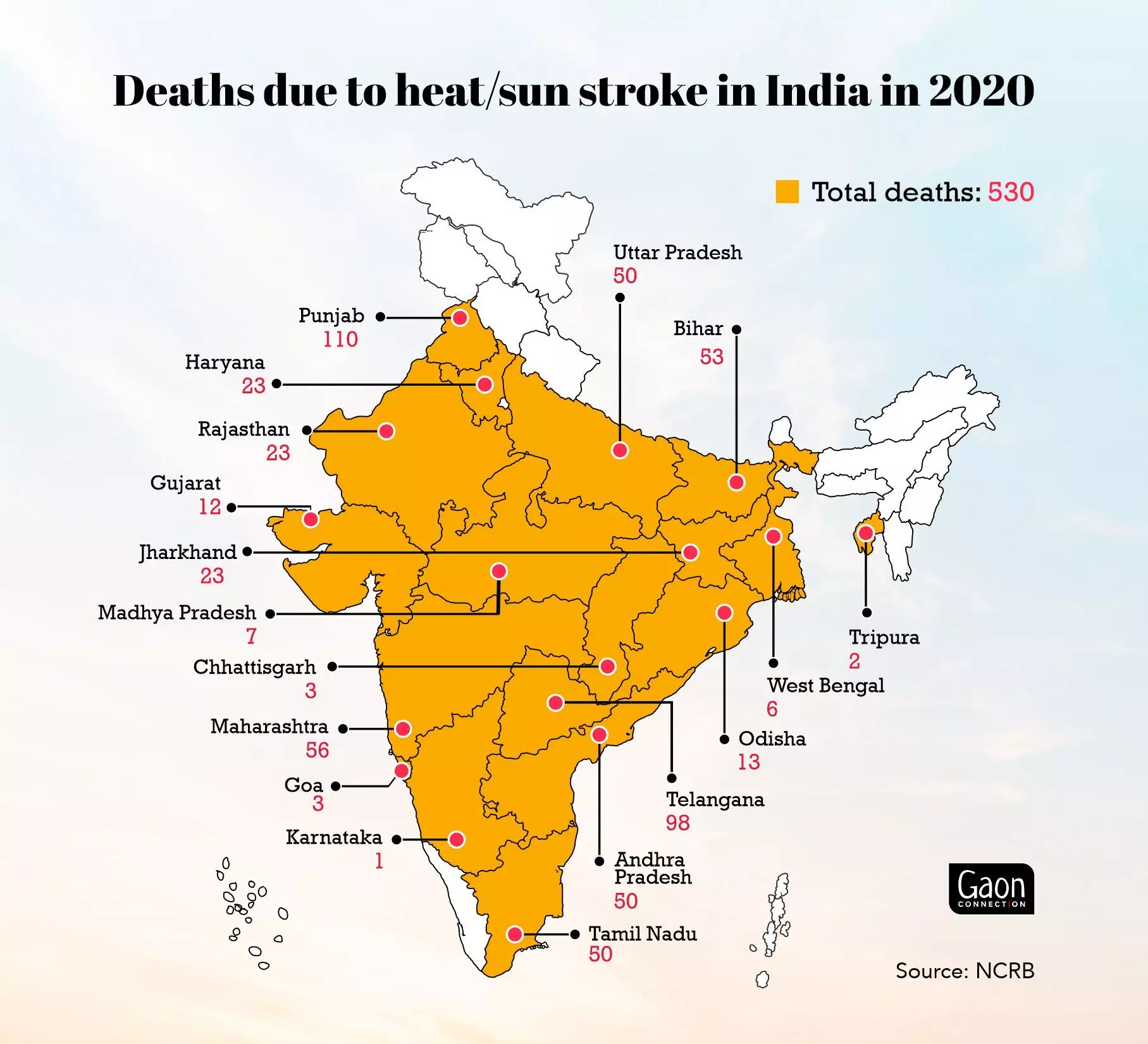

The latest NCRB data recorded 7,405 accidental deaths due to forces of nature across the country in 2020. Of this, 7.2 per cent of deaths were due to heatstroke (530 deaths).

“Our government is focussing on prevention. Through primary and community health centres by ASHAs and ANMs, we are raising awareness in rural areas. We are also running the National Programme on Climate Change & Human Health to check environment related diseases,” Ashok Kumar Pandey, additional secretary, health department, Government of Uttar Pradesh, told Gaon Connection.

In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, 254 cases and two deaths due to heat related illness were reported in 2019. The highest number of cases — 89 — were reported in Gautam Buddha Nagar district. It was followed by Chandauli (55), Mahoba (26), Auraiya (20), Mathura (13).

In the following two years of the pandemic, three cases were reported in 2020 and no related cases of heat related illness were reported in 2021, shows the state-level data accessed by Gaon Connection.

Satish Tripathi, state advisor, Uttar Pradesh health department told Gaon Connection that the report on heat stroke cases in 2022 will be out only in August this year. “These cases are reported by the primary health centres, community health centres and district hospitals,” Tripathi said.

Rising heat and the prolonged heatwaves are affecting productivity of rural Indians. Photo: Mohammad Salman

The official informed that an action plan to tackle heatwave related illness and prevent deaths is prepared based on the number of cases reported. The data helps the state and district administrations to prepare a heatwave action plan at the regional level to build resilience infrastructure, develop early warning infrastructure, and create public awareness.

Parag Talankar from SEEDS India said that heatwaves are not merely silent killers but full fledged disasters. “Earlier heat waves were not considered a disaster. But now according to the NDMA (National Disaster Management Authority), the heatwave is also a disaster and ever since the heatwave has been classified as a disaster in 2016, as of now 22,000 deaths have been officially registered with the NDMA due to the heatwave,” Talankar said.

“We need to understand how heat stress affects the health system in the long run. Such cases are going to increase the health budget within rural households. Heat stress is a big and slow problem that needs to be addressed. But, at the moment we are unable to map it or quantify it in any significant way,” Mohanty of CEEW, said.

Watch Also

What can be done?

Ashok Kumar Pandey, additional chief secretary of the UP health department suggested ways to prevent the heat related illness. “We can prevent diseases by protection from health exposure, avoid going in the sunlight, if it is mandatory then wear full sleeve clothes and keep your body hydrated,” said the official.

“Along with water, other liquid diets should be preferred to retain electrolytes inside the body. People are advised to take meals frequently, prolonged thrusting should be strictly avoided,” he added.

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), the magnitude of human costs from heatwaves can be reduced if adequate emergency prevention, preparedness, response and recovery measures are implemented in a sustainable and timely manner.

“Heatwave action plans are there. But more synergic efforts are required. Heatwaves are a natural disaster and the government needs to build resilience. Many reports suggest how heatwaves are going to increase in the country. Heatwaves are not only about day time but night times are also getting affected. These days nights are also very hot,” said Talankar.

Suggesting long term solutions, he said: “The government should be more proactive in converting discussions into actions. Revive natural water resources such as ponds and lakes for survival and groundwater recharge, promotion of water harvesting, plantation of trees, and including environment awareness in school curriculum.”