Pradeep Khoja, now 36, has grown up watching the laborious process of jeera farming on his ancestral farmland. Started by his grandfather, continued by his father and now Khoja, jeera (cumin) has been the choice of the crop which fits well with the dry, scarce rainfall climatic conditions of Pali in Rajasthan.

But despite the generational stronghold over the dos and don’ts of jeera farming, the farmer from Pali has halved the land under the jeera cultivation — from 2.5 hectares to 1.2 hectares (ha). Reason: Growing risk, high input costs, and mounting losses, Khoja told Gaon Connection. He has diverted the remaining land to grow raido (mustard), another rabi crop, he said.

Like Khoja, Lala Saran from GuraHema village in Chitalwana tehsil of Jalore district has reduced land under cumin cultivation from 60 bighas (1 bigha = 0.13 ha) last year to 40 bighas this year, and took a chance with sarson [mustard].

“Pichle saal poora jeera jal gaya [The whole harvest got wilted last year]. The hailstorms and erratic climate hit the cumin hard, a climate-sensitive crop. Against an expected 250 boris, I could get only 50 boris,” Saran sighed. Saran’s one bori carries 60 kgs of cumin.

Farmers in Rajasthan, the top second cumin producing state of India, are moving away from jeera cultivation. Cumin production has registered a drop. Predictably, the price of jeera has hit a new record.

Last week, on January 5, jeera cracked at an all time high — Rs 28,500 per quintal (1 quintal = 100 kgs) as down price and Rs 35,500 a quintal] as high price — in Unjha spice market of Gujarat. Unjha APMC (Agricultural Produce Market Committees) is Asia’s largest spice market and is a well known commercial centre for trade in cumin.

The market secretary, RK Patel told Gaon Connection that it is the highest rate the spice has hit ever since the time Unjha market came into existence about seven decades ago.

“It is last year’s stock which the vyaparis are taking out. The supply is low and demand is high in the global market putting cumin on the world map,” Patel said.

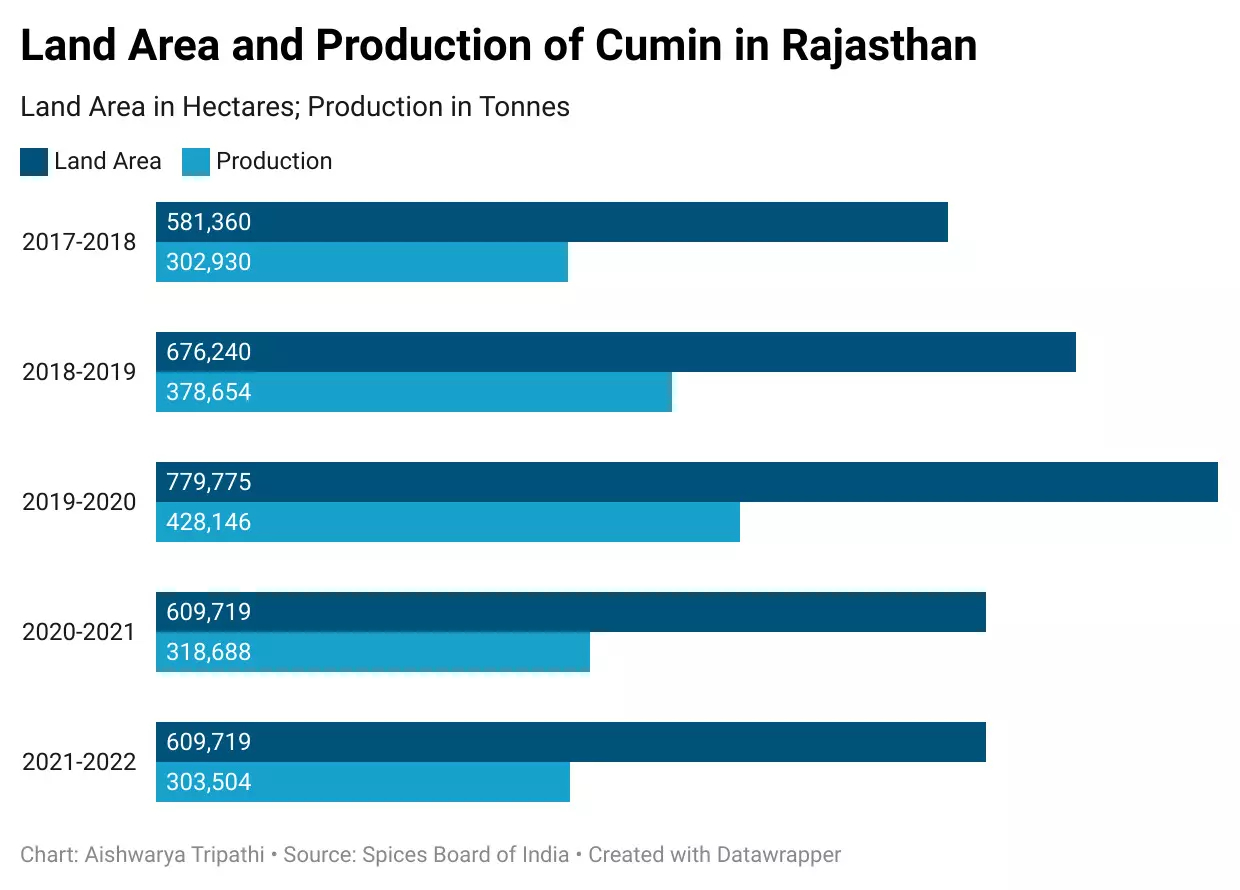

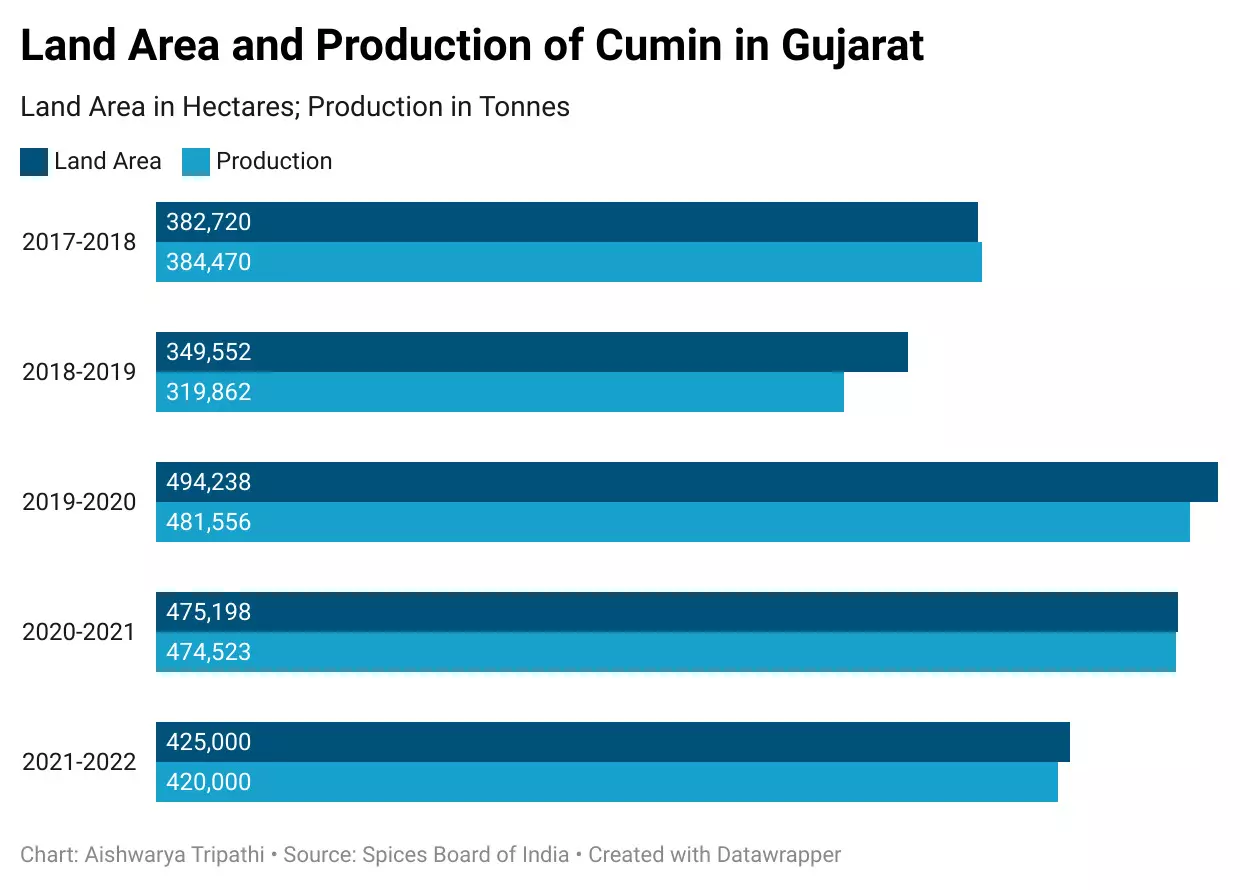

Drop in cumin production in Gujarat and Rajasthan

India is estimated to produce more than 70 per cent of the world’s cumin. In 2021-22, approximately 1,036,713 hectares of land in the country was under cumin cultivation, which yielded 725,651 tonnes cumin seed. This is lower than the country’s cumin production in the last two years — 795310 tonnes in 2020-21 and 912040 tonnes in 2019-2020.

Gujarat and Rajasthan are India’s two top cumin producing states with 99 per cent of the share in national production. In 2021-22, Gujarat contributed 420,000 tonnes and Rajasthan produced 303,504 tonnes, respectively.

According to data from the Spices Board of India, which comes under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, both the states have seen a downward trend in production of the spice as well as the land area under cumin cultivation in the past three years from 2019-20 to 2021-22.

Gujarat saw a drop in production from 481,556 tonnes in 2019-2020 to 474,523 tonnes in 2020-2021 and further to 420,000 tonnes in 2021-2022 — a cumulative drop of 12.78 per cent.

The bordering state Rajasthan has a larger drop — from 428,146 tonnes in 2019-2020 to 318,688 in 2020-2021, further down to 303,504 tonnes in 2021-2022 — a cumulative drop of 29.11 per cent (see graph).

Climate change to blame?

“The production is completely dependent on the climate. The recent shift in climate patterns is impacting the apt weather requirements for cumin. The crop needs low temperatures, non-cloudy weather but now even winters have higher temperatures than usual,” Abha Parashar, Assistant Professor of Agronomy, Agriculture University, Jodhpur explained.

Devendra Patel, Chairperson, Federation of Indian Spice Stakeholders seconded Parashar and said that climatic changes have hit cumin yield: “Where both Gujarat and Rajasthan were witnessing an average yield of 530 kg per hectare from 2018 to 2021, it dropped by 100 kg per hectares to 445 kg per ha in 2021-2022. The germination was severely impacted due to above normal temperatures in the winter season,” Patel told Gaon Connection.

Drop in production has led to a gap in demand and supply because of which cumin is trading at an all time high rate. “Last year in March 2022, the carry forward stock was 28 lakh bags [one bag weighs 55 kgs], whereas this year we had 12 lakh bags at the beginning of January, which will further come down to six lakh bags in March. The carry forward stock is almost one-fourth as compared to last year,” said Patel.

Lala Saran(extreme left) from GuraHema village in Chitalwana tehsil of Jalore district has reduced land under cumin cultivation from 60 bighas (1 bigha = 0.13 ha) last year to 40 bighas this year, and took a chance with mustard. Photo by arrangement.

“The average yield of past years has been 85 lakh bags, but in 2021-22 it was just 50 lakh bags. Including 28 lakh bags of previous year, we had 78 lakh bags in 2022, out of which 35 lakh were used domestically and 31 lakh were exported. On an average the domestic demands touch 42 lakh bags,” he added.

“Obviously, the high price is due to low production, lesser land area under cumin cultivation and high global as well as domestic demand,” said Parashar.

According to Patel, “The next 1.5 months will be crucial for this crop, and maybe if the temperature remains low, the yield can still pick up.”

Also Read: Virus Alert: Papayas in Barabanki and Sitapur succumb to a ringspot virus

Will an all-time-high price benefit cumin farmers?

Khoja’s jeera harvest is not ready yet. The weeding process in his fields is in full force and he is keeping fingers crossed to fetch at least 28 boris of the spice from 1.25 hectares. Fingers crossed because last year too he had expected to obtain 40 boris of harvest but after the climatic bash and a new wilting disease, locally called as piliya, he had only three boris in hand. Each sack holds 50 kgs of the spice.

“Jeera is a risky choice, or more so a gamble. An average jeera plant is 1.25 feet in height; in my fields it was two feet tall last year. Par paki hui fasal kharab ho gayi thi [A ripe harvest got ruined]. The piliya pest wiped out the entire field and I could not even extract the input costs, forget about profits. There was no pesticide available to fight this infestation,” said a disappointed Khoja.

Khoja sells his produce in a local market 25 kms from his village Nimbol in Jaitaran tehsil, in Bilara mandi, Jodhpur, which fetches him lesser price as compared to Unjha spice bazaar in Gujarat — 250 kms away from Khoja’s village. On January 5, when Unjha’s high price for cumin was Rs 7,100/ 20 kgs, Bilara mandi offered Rs 5,600/ 20 kgs.

Pradeep Khoja from Nimbol village in Jaitaran tehsil of Pali district has reduced land under cumin cultivation from 2.5 hectares last year to 1.2 hectares this year. Photo by arrangement.

Unlike Khoja, Lala Saran from Jalore transports his cumin 200 kms away to Unjha for sale in the hope of better market rates.

“Every year the rates are higher before the farmers like me reach Unjha mandi with their jeera produce. But this year it’s a bit too high. No farmer I know has the ready harvest now, it is the businessmen who have stored produce from last year and are getting such high prices. By the time we take our fasal, the international market needs would be sufficed for and the rates would drop,” Saran complained.

“Last year the vyaparis could get Rs 20,000 for a quintal, but we had got only Rs 15,000 per quintal of cumin produce,” he added.

Cumin farmers like Khoja and Saran don’t have any storage space for their produce to wait out the market rates to soar and make profits. In addition to the woes, cumin carries no Minimum Support Price (MSP), unlike mustard, an oilseed.

Also Read: New cumin variety to take lesser time to yield, pest-resistant; input costs to reduce as well

Growing jeera: A herculean task

To start with, jeera seeds have to be completely dry to sow, or else the seed doesn’t rupture. Khoja had bought the hybrid seeds available under the bannership of Ganesh and Dinkar from the market at Rs 35,000 per quintal.

The land preparation is tricky too. The fields have to be finely tilled or else the crop doesn’t expand properly, which means more ploughing.

“We can not reuse the cumin seed from the harvest as it will contain some humidity. Even if we dry it, it can never be as dry as needed to grow a healthy crop, thus it has to be bought. Why take the risk?” Khoja said. Comparatively, owing to no moisture-related risks, mustard seeds can be acquired from the previous harvest itself.

Cumin is a women labour intensive crop, which requires them to squat and manually weed out the unnecessary plants growing alongside jeera. The process is locally called nirayi-godayi. During the harvest time too, the women labourers pick out the dry jeera shrubs and collect at the designated area in the field — heaping them into a spice mountain.

“I had to call upon almost 100 labourers for the farm work in my jeera field last year, costing me about Rs 350-400 as a daily wage per labourer. All that into loss,” Khoja signed.

Khoja’s loss and his diversion to mustard, also means lesser work for these women labourers. Unlike cumin, mustard doesn’t require any thorough weeding, as only the upper part of the crop is cut and utilised, mostly done by men.

Sixty-year old Pappu Devi, a grandmother to 13 children, works as a farm labourer in Khoja’s field. Devi has a joint family, which means too many mouths to feed and her income makes a difference to meet the needs of her household. Cumin farming ensures her regular work, which if absent, Devi has to resort to MGNREGA to earn her wages. Last year, she had availed 35 workdays under the rural employment scheme against a promised 100 days.

Lesser acreage under cumin over years means lesser work available for the women labourers in the cumin producing belts of Rajasthan and Gujarat. Photo by arrangement.

Sushila Devi, 40-year-old farm labourer, also works at Khoja’s farmland. She said that she finds 15-20 days of employment per month during the crop cycle of cumin. The reduced land area under cumin has reduced her work days too, she complained.

Also Read: Rural women add spice to their livelihoods

Switching over from jeera to mustard

Parashar, Assistant Professor of Agronomy, Agriculture University, Jodhpur explained to Gaon Connection: “Owing to its short height, cumin requires tremendous weed management, which mustard doesn’t. It is a highly sensitive crop, which is prone to more infestation, needs more pesticides, reacts quickly to any temperature change and extracts more nutrients from the soil. In a hectare, a farmer will get 25 quintals of mustard but only 15 quintals of cumin.”

“Mustard, on the other hand, is easier on all fronts, except the market price because unlike cumin it is not a commercial commodity,” she added.

She recalled a folk song: ‘Jeero jeevro bairi re, mat bao na paranya jiaro’, which describes the high sensitivity of the spice.

Last year, Khoja had sowed four kg of cumin seeds in a bigha [0.25 hectare] of land, which produced only 750 gms in return. “It gets easily attacked by moila keet, which requires herbicide sprinkling at least five times through the crop cycle. After the last irrigation process, again the weeds had to be plucked out. The ratio of weeds to cumin is almost thrice. The threshing is also done manually.”

Though Khoja doesn’t have an exact lekha-jokha of his input costs but for pesticides alone, he had paid an average of Rs 27,000 per hectare. With 2.5 hectares under jeera cultivation, this costs amounts to Rs 67,500.

A report by Indian Council of Agricultural Research estimates the per hectare input cost for cumin as Rs 61,817.32. Going by this figure, Khoja’s input cost for 2.5 ha would be around Rs 1.54 lakh.

Agricultural experts point out that rotating crops on the same patch of land is a healthier practice. Mahendra Kumar Choudhary, Subject Matter Specialist, Agronomy in Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Pali, told Gaon Connection, “Crop rotation is always good. Repetitive cumin cultivation deteriorates soil nutrients and will reduce the produce after a point of time.”

Parashar, the assistant professor in Agriculture University, Jodhpur echoed his views.

Pointing out the urgent need for research on a new variety of cumin, Parashar indicated that “the farmers are using the GC 4 variety of cumin which came in 2007. This was known to be an anti-wilting variety but now farmers are facing the wilting issues even with GC 4. Any variety would perform good for a maximum of ten years and would lose its capacity beyond that.”

Meanwhile, low production has affected cumin export too. “While the average annual cumin export stands at 2.5 lakh tonnes, in 2022-2023 it was down to 1.7 lakh tonnes,” Patel pointed out.

Top importers of cumin seeds across the globe are China, Bangladesh, US, Egypt, UAE, and Saudi Arabia; together accounting for more than half of the import demand for the seeds in 2019. The major supplying contenders are Afghanistan, Syria and Turkey.

Khoja and Saran bemoaned that they only get to know about the prices for their produce after it reaches the market in March.

“Even if the prices are low then, it’s not like we have a choice. We will sell at whatever price we are offered,” Khoja said.

Cumin farmers of Rajasthan like Khoja and Saran are hoping that the prices continue to remain on the higher side even in March when they will set out to sell their harvest.